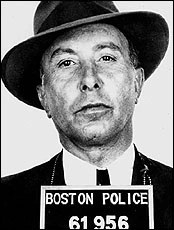

Gaspare Messina was the most powerful mafioso in Boston from around 1916, when Gaspare Di Cola, Boston’s “Lemon King,” was killed, until his retirement in 1932. He received Nicola Gentile in 1921, and served as the provisional boss of bosses for the last months of the Castellammarese War. Even after his retirement, Messina was treated with high regard by other mafiosi, who came to “kiss the ring” until his death in 1957.

Messina was born in Salemi, in the province of Trapani, in western Sicily, on 6 August 1879. His father, Luciano, was a peasant, called either a villico or a contadino in civil records.

Luciano died when Gaspare was only eleven. And although he claimed in 1905 that his father had been, in life, a resident of Santa Ninfa, a few miles from Salemi, I can find no evidence Luciano Messina ever lived there. He and his wife, Gaspara Clementi, married in Salemi and had three children, all born in the same town. After Gaspare, in 1879, there were two daughters named Vita, in 1883 and 1884, which means that the older one died in infancy. After that, Luciano disappears from the record, but it’s not hard to guess where he went next.

When Gaspare Messina’s parents married, they both indicated they were native residents of Salemi. Luciano’s death was recorded there in 1890. But as it turns out, he hadn’t been living as a rich man in Santa Ninfa, as his son’s marriage would later suggest. Instead he was a prisoner, dying in the Casa Penale in Noto, in Syracuse province. Even in death, his occupational status was recorded as “contadino,” or “countryman”: in other words, a peasant.

His father’s death record sheds some light on Gaspare’s early exposure to the criminal life, but not his relationship to the nearby comune of Santa Ninfa, where he married. At marriage, Gaspare called himself a borgese—a member of the propertied class—and said his late father had lived in Santa Ninfa. Adding to the list of cryptic, unsubstantiated claims from Messina on official forms, when he petitioned for naturalization in New York in 1930, he wrote that he married Francesca in Salemi, and that she was born there as well. Was he intentionally misleading American authorities, or was his pattern of misinformation the result of stories he was told about his father?

Gaspare’s Santa Ninfa relatives were vital to his network. His wife, Francesca Riggio’s father was a shepherd and goatherd who was, at least once, taken for a borgese by the midwife, suggesting he was a relatively successful herdsman. Men who grazed animals for a living had to cover a lot of ground and keep themselves and their valuable flocks safe from thieves while they were far from towns and the help of others. Traveling through western Sicily was so dangerous that to do so safely became a sign of good relations with the Mafia. It’s no accident that the rural entrepreneurial trades like herding and transport were closely associated with the Mafia in Sicily. The father of one of Messina’s successors in Boston, Joseph Lombardo, was a carter from the same town as Gaspare Messina.

Gaspare and Francesca went to Messina’s “cousin” in Brooklyn, New York. He was actually Francesca’s maternal first cousin, a barber supply salesman named Francesco Accardi. Richard Warner, writing for Informer in 2011, cited two personal sources who said the newlywed Messinas stayed in Brooklyn as long as they did, when they’d only intended to visit, because she became pregnant. The ship manifest doesn’t indicate their intentions, whether for a visit or protracted sojourn. The couple did not have a child the following year. In 1910, two of Francesca’s younger siblings, possibly Mariangela (she’s recorded as “Jeanette Rego”) and Pasquale, lived with them. The younger Riggios told the census taker they emigrated in 1905, the same year as the Messinas.

Thomas Hunt notes that historians originally assumed Gaspare Messina’s father was named Salvatore, since that was the name of his first son, born in Brooklyn in 1911. I think instead it might be a gesture of gratitude for his existence. Remember that Francesca was pregnant once before, but their first child wasn’t born for six years. The next two sons, Luciano and Vito, were named for their grandfathers, according to the tradition.

Gaspare was embroiled in local Mafia politics from his early years in Brooklyn. He was associated with the cosca headed by Nicola Schiro, from Roccamena, but he’s also described by Warner as one of the Palermitan Salvatore D’Aquila’s loyalists. D’Aquila is said to have placed several important mafiosi in other cities. According to Warner, he sent Messina to Boston deliberately to rise to the top of its underworld and support him from afar.

Some say that the “Lemon King,” Gaspare Di Cola (1866-1916) of Termini Imerese was Boston’s first Mafia boss, and his murder either orchestrated by or taken advantage of by Messina, who arrived in Boston the year before Di Cola was killed. Other suspects in Di Cola’s murder include his common-law wife’s ex-husband, whom she’d recently divorced, her son, who had long opposed his mother’s relationship, and whoever was sending Di Cola Black Hand letters. As a wealthy and successful business owner—Di Cola was a produce wholesaler—he was a highly visible target for extortion attempts.

Many general sources on the origins of the Boston Mafia credit Messina with starting the organization in 1916, but in fact little is known about his criminal activity or partnerships, so it’s hard to say exactly when he established a Mafia gang or what that looked like. He moved to Boston by 1915, when Vito was born. In Brooklyn and then in Boston, Gaspare owned bakeries. He avoided legal trouble, though some of his associates did not, and that is one way in which he’s been identified. More importantly, Nicola Gentile wrote about him.

Gentile met Gaspare Messina while visiting Boston in 1921. He had no doubt he’d met a powerful man, and one who put him immediately into an uncomfortable position. Making the flimsiest of excuses, Gentile left his audience with Messina, left Boston, and went all the way back to Brooklyn to see Messina’s old boss, Nicola Schiro.

In 1921, D’Aquila had hits out on Giuseppe Morello and nearly a dozen of his closest associates. Gentile had just returned to the northeast from a few years of bootlegging in Cleveland, Kansas City, and Pittsburgh. Having survived a murder attempt in Cleveland, he was loathe to return there; yet D’Aquila threatened to send Gentile to join the Cleveland Mafia as one of his supposed loyalists. (D’Aquila’s opponent, Joe Masseria, was also trying to stock other Mafia gangs with his people: in Cleveland, in particular.) Unknown to D’Aquila, Gentile had decided to back Masseria. According to Warner, Gentile joined Schiro’s Family to prevent being conscripted by D’Aquila, and only then did he go back to see Messina and apologize.

Gaspare Messina had proposed a banquet in Gentile’s honor in Boston. Why did that so unnerve the accomplished mafioso that he left town and joined a crime family in Brooklyn? It might have alerted D’Aquila that Gentile had switched sides.

In 1923, Secret Service discovered Messina was involved in a counterfeiting operation managed by Salvatore Lonarti (or Leonardi) on the North End in Boston. He took a trip to Sicily to evade their surveillance. On his return, however, he accompanied the noted mafioso Antonino Passananti and his family to New York. Passananti was one of the suspected gunmen in the assassination of New York police detective Joseph Petrosino.

Joseph Lombardo moved to Boston in 1925 and started an import business. He is usually described as having been Messina’s underboss, but when this merger may have occurred is uncertain. Lombardo formed his own group in the North End, where Messina’s home and bakery were, and took over the Italian lottery. Vincent Teresa, who was a soldier in the Boston Mafia, describes the criminal landscape in his memoir. Instead of a single Mafia Family with one boss, there was a hierarchy of mafiosi recognized by their power, each with his own gang.

In this regard the model that best fits is Hess’ mafia landscape in which up-and-coming mafiosi compete and sometimes align with more established mafiosi with large, powerful gangs. When these gangs were united in big American cities like New York and Boston, they functioned as crews with captains. Before that time, they had regional and national assemblies at which a council of equals (but with one acknowledged boss of bosses) resolved disputes and made agreements. The part of the hierarchy above the boss shows more variation, probably because it’s the only non-native part of the Mafia. In Sicily, there was no need for super-cosca administration; there were only neighboring mafiosi with whom to deal on an ad hoc basis.

Messina opened a wholesale grocery on Prince Street with two partners around the same time Lombardo arrived in Boston. A couple years later, he moved his family to Somerville, Massachusetts, in the suburbs, though he continued to own businesses in the city. From their home at 49 Pennsylvania Avenue, “Don” Gaspare would continue receiving guests and resolving disputes even after his retirement in 1932.

But in 1930, Messina was still the most powerful Mafia boss in Boston. Meanwhile, events in New York once again threatened to draw him into deeper waters. D’Aquila was killed in 1928. Now, the Castellammarese War was raging between factions led by Masseria and his new challenger, Salvatore Maranzano from Castellammare del Golfo. Maranzano came up in Nicola Schiro’s gang in Brooklyn, which had many members from Castellammare. In 1930 Schiro crossed Masseria, who extorted him and forced him to retire to Sicily. Maranzano took over Schiro’s gang.

Messina petitioned for US citizenship early in the year, using a Manhattan address, while at the same time his family appeared in the US census, living in Somerville. His petition was granted in July. That month, Vito Bonventre was killed. He was one of the most successful bootleggers in Brooklyn, a Castellammarese who had been a member of The Good Killers, and was in Schiro’s crime family. Maranzano blamed the murder on Masseria’s men. Masseria’s consigliere, the former boss of bosses Giuseppe Morello, was killed in August.

In December, at the Mafia’s annual assembly, Masseria was stripped of his “boss of bosses” title and Messina, who was well liked, was given the position. Maranzano, who had engineered this, resisted the assembly’s efforts to broker peace, and instead let it be known that there would be no consequences for any of Masseria’s own men who killed their leader. Luciano took him up on it and “Joe the Boss” was killed in April 1931. Maranzano was elected the new boss of bosses.

In Boston, Lombardo’s star rose as he eliminated the threat of Irish thieves in the Gustin Gang, at the end of 1931. Gustin gangsters had been robbing bootlegging trucks. Lombardo was arrested for the murder of two of their members but released by a grand jury.

Subscribers can read more about the Gustin Gang on Patreon.

In 1932, Messina stepped down from his position as a Boston mafioso. He worked with two of his business partners from the import company at expanding operations throughout the region.

Without Messina, Filippo Buccola became the most important boss in Boston. Lombardo served as his consigliere as Buccola merged his gang in Boston with Providence. The Mafia in Providence, Rhode Island was formed by Frank Morelli around the time Messina appeared on the scene in Boston. Vincent Teresa describes Joseph Lombardo’s role as a powerful one in this transition period. He continued to be the man others sought for permission and advice, throughout New England, into the 1950s.

Buccola retired to Sicily in 1954, and career criminal Raymond Patriarca took over all the Italian rackets in New England, barring portions of western Massachusetts that were controlled by Sam Cufari. He moved the base of the combined Boston and Providence mafias to Rhode Island in 1956.

In April 1957, Nicola Schiro died in Sicily. On 15 June, “Don Gaspare” died suddenly from heart disease at his home in Massachusetts.

Under Patriarca’s rule, Buccola’s right-hand man, John Guglielmo, was pushed aside by Gennaro “Jerry” Angiulo. The Angiulo brothers grew up on Prince Street and ran nightclubs and restaurants. Jerry became the boss of Boston, and Patriarca’s underboss, around 1962. He and his captains collectively controlled all aspects of theft, gambling, and drug traffic in the greater Boston area.

Patriarca Sr. died in 1984 and was succeeded by his son, Raymond Patriarca, Jr.

Patriarca Jr’s underboss, William Grasso, who’d been a protege of Patriarca Sr., made Frank Salemme his right-hand man. However, Salemme was secretly allied to Whitey Bulger, and plotted to take over the Patriarca Family. Grasso was killed in the Springfield area in June 1989.

Around this time, Silverman reports, two Patriarca men who wanted to resume their old territories after going away were told repeatedly by leadership that it wasn’t going to happen. What they did next demonstrates the complexities of power among Mafia Families. They took their complaint “up the ladder” to the Genovese Family. “The Patriarca family has always been controlled by New York’s Genovese Family,” Silverman said. “In fact the Genovese had a crew that operated in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their Springfield crew was headed by Genovese captain, Adolfo (Al) Bruno.”

The Genovese Family has controlled Springfield, Massachusetts, since the mid-1920s. They’re usually described as a more powerful ally of the Patriarca Family, not as its parent organization. The periodic jostling of Patriarca and Springfield-Genovese associates in contested areas of western Massachusetts and northern Connecticut tells me there is not a clear-cut hierarchy among these entities, but that everything is up for negotiation. To wit, the merging of Boston and Providence.

Angiulo went to prison for racketeering in 1986 and died in 2009, two years after his release, at age 88.

Salemme, Bulger, and others were indicted together in 1995 for extortion, leading to a new takeover attempt by Salemme’s opponents among the captains in the Patriarca Family. The FBI went after fifteen of the opposition, but none of the charges stuck. Luigi Manocchio became the Family’s boss in 1996. That year, he was indicted with 43 others in a burglary ring. In 1999, at the start of the trial, he secretly cut a deal for probation.

Power in the crime family moved back to Boston in the 2010s. Peter Limone became the boss in 2009 when Manocchio got into trouble again, this time for extortion. Limone had been a troubleshooter for Jerry Angiulo. He was set up for a murder by the corrupt FBI handlers working with Bulger, and ended up serving 33 years for a crime he didn’t commit. Mike Albano, before he was Springfield’s mayor, served on a probation committee and supported Limone’s release.

Limone succeeded Manocchio in 2009 and two years later Antonio DiNunzio became acting boss. He went to prison for extortion in 2012 and the new acting boss was Antonio Spagnolo.

When Antonio DiNunzio’s older brother, Carmen, was released from prison in 2015, he returned to his crew in the North End of Boston. Limone remained the nominal boss through a long bout of cancer. He died in 2017 and Carmen DiNunzio became the new boss. He is the current leader of the Patriarca crime family.

Succession of Bosses in Boston

Gaspare Di Cola (1866-1916)

Gaspare Messina (1879-1957)

[uncertain] Joseph Lombardo (1893-1969)

Filippo Buccola (1886-1987) [move to Providence]

Raymond Patriarca, Sr. (1908-1984) / Gennaro “Jerry” Angiulo, underboss (1919-2009) [Boston]

Raymond Patriarca, Jr. (1945-)

Frank Salemme (1933-2022)

Luigi Manocchio (1927-)

Peter Limone (1934-2017)

Antonio DiNunzio (1959-) [acting boss]

Antonio Spagnolo (1942-) [acting boss]

Carmen DiNunzio (1957-)

Sources

Claffey, K. (1990, March 28). WMass ‘soldier’ gives up – Indicted in mob sweep. The Republican/Union-News. P. 1.

Critchley, D. (2009). The origin of organized crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. Routledge.

Cullen, K. (1970, January 19). One lingering question for FBI director Robert Mueller. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/1970/01/19/one-lingering-question-for-fbi-director-robert-mueller/613uW0MR7czurRn7M4BG2J/story.html

Hunt, T. (2021). Messina, Gaspare (1879-1957). The American Mafia [website]. http://mob-who.blogspot.com/2016/08/messina-gaspare-1879-1957.html

Joseph Lombardo. Project Marino (website]. Retrieved 3 March 2023 from

https://projectmarino1996.wordpress.com/boston-underworld-timeline/joseph-lombardo/

Murphy, S. (2009, August 31). Gennaro ‘Jerry’ Angiulo, 90, New England mob underboss. [Obituary]. The Boston Globe. http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/obituaries/articles/2009/08/31/gennaro_jerry_angiulo_90_new_england_mob_underboss/

New England Mafia boss Peter Limone passes away. (2017, June 19). AboutTheMafia. http://aboutthemafia.com/new-england-mafia-boss-peter-limone-passes-away

Silverman, M. and Deitche, S. (2012, March 17). Rogue mobster: the untold story of Mark Silverman and the New England Mafia [book excerpt]. Strategic Media Books. http://crimemagazine.com/rogue-mobster-untold-story-mark-silverman-and-new-england-mafia

Valin, E. Vinnie Teresa cooperated much earlier than he let on. The American Mafia [website]. https://mafiahistory.us/rattrap/vinteresa.html

Warner, R. N. (2011, October). Gaspare Messina and the rise of the Mafia in Boston. Informer journal. Pp. 4+.

The patricia family was NEVER controlled by the genovese family. It was the opposite. The genovese family got their asses whooped in connecticut by grasso the underboss of Raymond Sr. The genovese family of springfield couldn’t compare to Raymond Sr. Springfield faction was jealous of Boston and providence and rated on guys who had buttons in New York City especially the Gambino family who never trusted them.It was just because they were so large at one time and Vito who was powerful in NYC was giving orders but over the years, all that declined and now they are nothing.

LikeLike

I don’t claim the Patriarca Family was ever controlled by the Genovese. I wouldn’t go the other way, though. You’re talking about one battle between two long standing gangs. That hardly makes your case.

LikeLike