What is a padrone, and how do they fit the mold of the classic mafioso? How did the padrone evolve in the United States into the gangster we recognize as Mafia today?

An example of the padrone is John Albano of Springfield, Massachusetts. He shows up in the story of his infamous niece, Pasqualina Albano Siniscalchi Miranda, the “Bootleg Queen” of Springfield’s Little Italy during Prohibition. His significance to her rise in the criminal underworld can’t be overstated. In fact, when I presented her biography at a genealogy conference recently, I began by introducing her uncle John, who was known before her reign as “the king of Little Italy.”

Who were the earliest bosses of Springfield, Massachusetts? Before Sam “Big Nose” Cufari was the boss of the Springfield Mafia, there was Carlo Sarno. Before Carlo, it was his sister-in-law, Pasqualina Albano. And before Pasqualina held the title, it was her uncle, Giovanni “John” Albano, who was the first mafioso of Springfield, Massachusetts.

John Albano wasn’t a bootlegger. He didn’t get into shootouts on Water Street (though he came very close in 1911) or hire thugs to intimidate laborers (like some other padroni we could mention). He was the kind of mafioso who resolved disputes and dispensed help and advice to his countrymen. Arguably, he didn’t need to bring in outsiders as muscle: he had four strapping and obedient sons to handle what John himself could not.

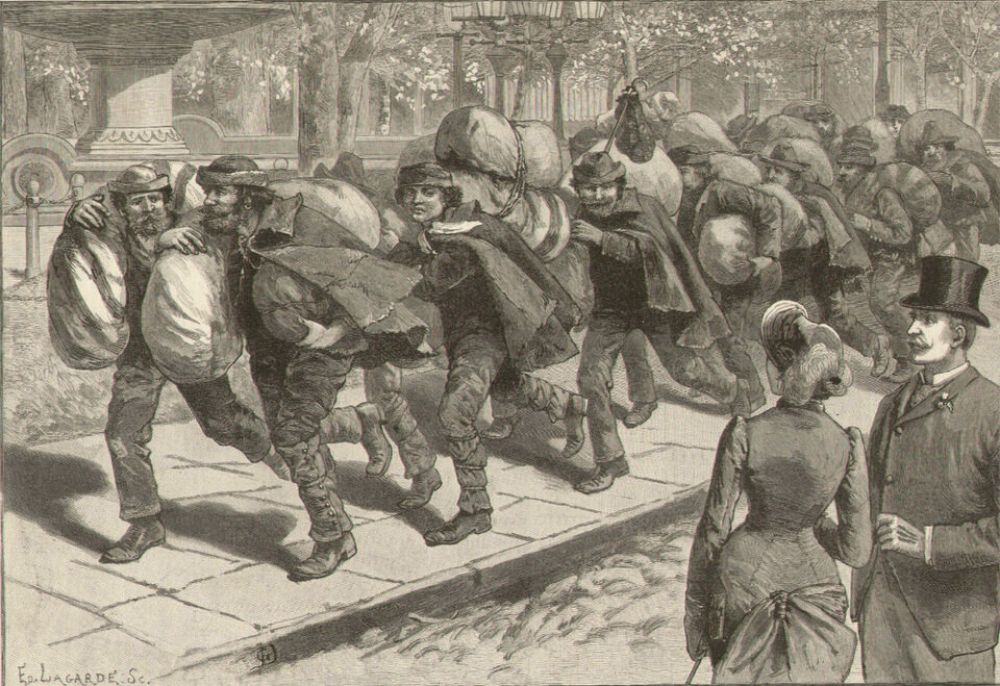

Albano was a “padrone,” a familiar figure in Italian settlements throughout the United States. On sugar plantations, in coal mining camps, mill towns, and railway hubs, in cities large and small, Italians came to find work, and many of them did so with the help of a padrone.

Mafiosi were brokers. [1] Brokers handle transactions, such as connecting a Louisiana plantation owner and rural Italian agricultural laborers, who would otherwise be unable to conduct this business directly. The reasons varied, including because the parties can’t find one another or are unable to communicate, or the transaction is too risky [2] for one of the parties, too byzantine, or unpleasant. Some of the original mafiosi in Sicily were gabellotti, large leaseholders who took on the risk and unpleasantness of managing large estates. Wealthy landowners preferred life in the city to farm management and small village life. Gabellotti not only accepted the lifestyle the landowner regarded as undesirable, they leveraged their position.

For centuries, the wealthiest and most powerful family in a village were also sought for advice, aid, permission, and to address grievances. They were the ones who were in a position to help, had the resources, and might be persuaded to use them. With landowners gone, not seen for generations on the land, the gabellotti took their place. They granted small leases to farmers, employed farm laborers and guards, and possessing more cash than anyone else in town, were also the closest approximation of a bank. Gabellotti loaned money to both small farmers, who to this day borrow cyclically, paying for seed with the harvest, and to their employers, the landowners, who were frequently land-rich and cash-poor.

The same term, padrone, is used in Italy to refer to gabellotti [3] and landowners [4] who manage their own estates, and to labor agents and bankers in America who served Italian immigrant communities. [5] By easing the transition for new immigrants, the padrone added grateful neighbors to his network: both the workers and the employers. And the padrone benefitted from both relationships.

Padroni didn’t have to charge employees for matching them with jobs: employers paid for this service, and the padrone had other ways of making money from workers. Patronage relationships are not a tit-for-tat situation. Patrons and clients understand that this is a lifetime bond, that there is a privileged end of the dyad and one that is subservient, and who occupies which pole. [6] Despite this inequality, both parties are beholden by their working friendship to help the other to the extent they’re able.

Giovanni Albano, born in 1847 in Bracigliano, Italy, came from the vast contadino class: people who, fifty years earlier, were peasants living under feudalism. [7] He came to the United States around 1880 as a laborer in railroad construction. Possibly some other padrone helped secure him this job, rented him a bed to sleep in, fed him and extended him credit until he began to earn.

But soon, Albano was the one welcoming his fellows from Bracigliano and putting them to work. He sold them their steamship tickets, rented some of them their homes and storefronts, and safeguarded their money. In those days, there was no FDIC, and even if there had been, it would have been out of character for contadini to trust a foreign institution over a man who was their padrone. [8]

Like many successful mafiosi, John Albano was a prominent businessman in his city. He owned a steam ship ticket agency, he was a labor agent and a bail bondsman, he represented a local brewery for many years, became a banker in 1905, and in the years before his death went into wholesale liquor sales with his son, Felix. John had extensive real estate holdings in the city, and a farm in Westfield. He was also a community leader: a marshall in religious parades, and the founder of social, religious, and civic organizations, among them the Mount Carmel Social Club, a notorious Mafia hangout where Al Bruno was killed in 2003.

It can be difficult to prove that someone fulfills the definition of a mafioso. Business success, bolstered by unethical methods ranging from intimidation, bribery, and blackmail to arson, assault, and murder, is a hallmark of the Mafia. But another definitive role of the mafioso is brokerage: the trusted middleman. In the Mafia, bosses monopolize brokerage positions, so those in his network bring opportunities to him. [9] John Albano was said to have brought a thousand people from his hometown to Springfield. Each of them was related only to him in this special way, like the leaves of an artichoke. [10] If in that thousand there were five or ten men who had the capacity to do violence and keep secrets, he would find out which ones they were and bring them in close.

And what evidence do I have for him doing this? His niece’s marriage to Carlo Siniscalchi. As the oldest male member of the family in Springfield, John would have been consulted in all matters concerning the family, including marriage. It may have been through his work as an agent for a brewery that he met a saloonkeeper in Brooklyn who was from a neighboring town in Naples. Or he might have become aware of Siniscalchi through his friendship with John’s son, Frank, who worked for the brewery as a teamster. [11] Carlo and Frank stood as best man in one another’s weddings.

While the couple indicated in a social column in the local newspaper their intention to live in Brooklyn after the wedding, before they were married, Carlo Siniscalchi petitioned the city of Springfield for permission to own three pool tables. John Albano owned a pool hall on Water Street — the center of Italian life in Springfield — most likely the same establishment where Carlo’s pool tables were installed.

Carlo Siniscalchi was a physically dangerous man, unafraid to use violence — or to manipulate violent men. Perfect for running a bar, a rowdy pool hall, an illegal card game, or a gang. All four of John Albano’s sons died young, two of them from alcoholism by 1917. John himself died in 1915 from stomach cancer. His passing left Carlo Siniscalchi in the best possible position to take control of vice on Water Street. From there, it was only natural that he expanded into bootlegging when Prohibition began.

A healthy Mafia gang balances legitimate appearances with criminal strength. Too far in either direction and the gang loses its violent power or its cover of respectability. Without community and political support or the healthy respect (or fear) of its criminal rivals, the gang dies: its members overtaken or incarcerated. The Mafia needs John Albanos at least as much as it needs Carlo Siniscalchis.

Springfield, Massachusetts, is not the only place in the United States where padroni were intimately connected with other practitioners of organized crime. In 1906, one of the earliest Mafia “blood feuds” in Los Angeles took the life of Joseph Cuccia, a respected leader of the Italian community who served as a court interpreter and mediated disputes between mafiosi.

Another padrone who fell victim was Antonio Saltaformaggio, married to Lucia Terranova, Giuseppe Morello’s half-sister. He was a labor agent in Louisiana when the Macaroni Wars heated up in New Orleans. His brother-in-law Santo Calamia led an offensive on behalf of two powerful mafiosi, and possibly in consequence of this, Saltaformaggio was found murdered in a canal in April 1903.

Notes

- Catanzaro, R. (1992). Men of respect: A social history of the Sicilian Mafia. Translation by Raymond Rosenthal. The Free Press (A Division of Macmillan, Inc.) New York. Print. (Original published in 1988)

- DellaPosta, D. J. (2017, May). Wise guys: closure and collaboration in the American Mafia. [Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University]. eCommons Cornell University. Ecommons.cornell.edu.

- Blok, A. (1974). The Mafia of a Sicilian Village, 1860-1960: A Study of Violent Peasant Entrepreneurs. Harper Torchbooks.

- Hess, H. (1998). Mafia & Mafiosi: Origin, Power and Myth. (E. Osers, Trans.). London: C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd. (Original work published 1973); Paternostro, D. (1994). L’antimafia sconosciuta Corleone 1893-1993. Palermo: La Zisa, P. 31

- Nelli, H. S. (1976). The business of crime: Italians and syndicate crime in the United States. The University of Chicago Press, p. 136

- Blok. Ibid; La Manna, F. (2019). Contiguità, interclassismi e rotture rivoluzionarie nella Sicilia borbonica. Realtà e rappresentazione di un incerto sodalizio tra opposizione politica ed elementi criminali. Diacronie. Studi di storia contemporanea : Mafia e storiografia. Premesse culturali e prospettive attuali, 39, 3/2019, 29/10/2019, URL: < http://www.studistorici.com/2019/10/29/lamanna_numero_39/ >. Both cite Franchetti’s concept of manutengolismo.

- Elizabeth Reuss-Ianni and Francis Ianni call the padrone system a “new feudalism.” Ianni, F. A. and Reuss-Ianni, E. (1972). A family business: Kinship and social control in organized crime. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Blok. Ibid; Catanzaro. Ibid.

- Xiao, Zhixing and Anne S. Tsui. (2007). “When Brokers May Not Work: The Cultural Contingency of Social Capital in Chinese High-tech Firms.” Administrative Science Quarterly 52:1–31.

- Catanzaro. Ibid.

- Teamsters, now synonymous with the truckers union, are over land transportation professionals, or carters. Before automobiles this work was done with teams of horses, mules, or oxen.