Three murders preceding “Diamond Joe” Viserte’s were the true beginnings of the war between Salvatore “Toto” D’Aquila and the Morello-Terranova Family.

These were the turbulent years after Giuseppe Morello was released from the federal prison in Atlanta in 1920, and before he became Joe “The Boss” Masseria’s counselor, which came to be called the Second Mafia War. Salvatore “Toto” D’Aquila, one of Ignazio Lupo’s capos in Brooklyn, had split from the Morello gang while Morello and Lupo were in prison, and during the Mafia-Camorra War, became far more powerful than his former bosses (Critchley, 2009; Waugh, 2019; Warner, Santino and Van ‘t Riet, 2014). Morello and Lupo’s return in 1920 threatened D’Aquila’s plans for total dominion over the underworld in New York City.

The Mafia Family that Giuseppe Morello returned to was a fraction of its size and under attack. Salvatore LoIacono of Marineo, who succeeded the Lo Monte brothers as custodians of Morello’s Family, resisted Giuseppe Morello’s return to power. It’s possible LoIacono had the support of D’Aquila (The Mob Archeologists, 2023). Morello appears to have had LoIacono killed in December 1920, but his loyalists remained cohesive and were a separate faction. Toto D’Aquila, New York City’s most powerful gangster, remained Morello’s principal threat.

The October 1921 murder of Vincent Terranova’s ally, Giuseppe “Diamond Joe” Viserte, is said to be the opening salvo in the war between D’Aquila and Morello, but three other murders that year were likely attacks by D’Aquila’s men on targets who were important to Morello.

The October 1921 murder of Vincent Terranova’s ally, Giuseppe “Diamond Joe” Viserte, is said to be the opening salvo in the war between D’Aquila and Morello, but three other murders that year were likely attacks by D’Aquila’s men on targets who were important to Morello (Dash, 2009, pp. 272-273).

The first casualty of the Second Mafia War was a driver ambushed in January 1921. Giuseppe Terranova was Giovanni Pecoraro’s chauffeur. Pecoraro was a wealthy, long-time criminal associate of Morello. At least two shooters were lying in wait for him, one of them inside the Interborough Ice Cream Company, owned by Morello associate Giuseppe Lagumina. A former business partner of Lagumina’s, Giuseppe Mantruzzi, was arrested and accused of hiring the shooters (Warner, et al).

Unrelated to Morello and his half-brothers from Corleone, Giuseppe Terranova was born in Partinico (Baptism of Joseph Terranova, 1893). He arrived in New York City in 1910, joining his brother on the east side of Manhattan (Manifest of the SS Virginia, 1910). In addition to working as a driver, Terranova ran a feed store with his employer’s wife (Joseph Terranova draft registration, 1917; Joe Tarranova petition for naturalization, 1920; Pecoraro household, 1920; Terranove household, 1920). It’s plausible that, given their associations, the feed store was a front for illegal alcohol distribution, lotteries and other forms of gambling, the movement of counterfeit money, or the laundering of illegal earnings.

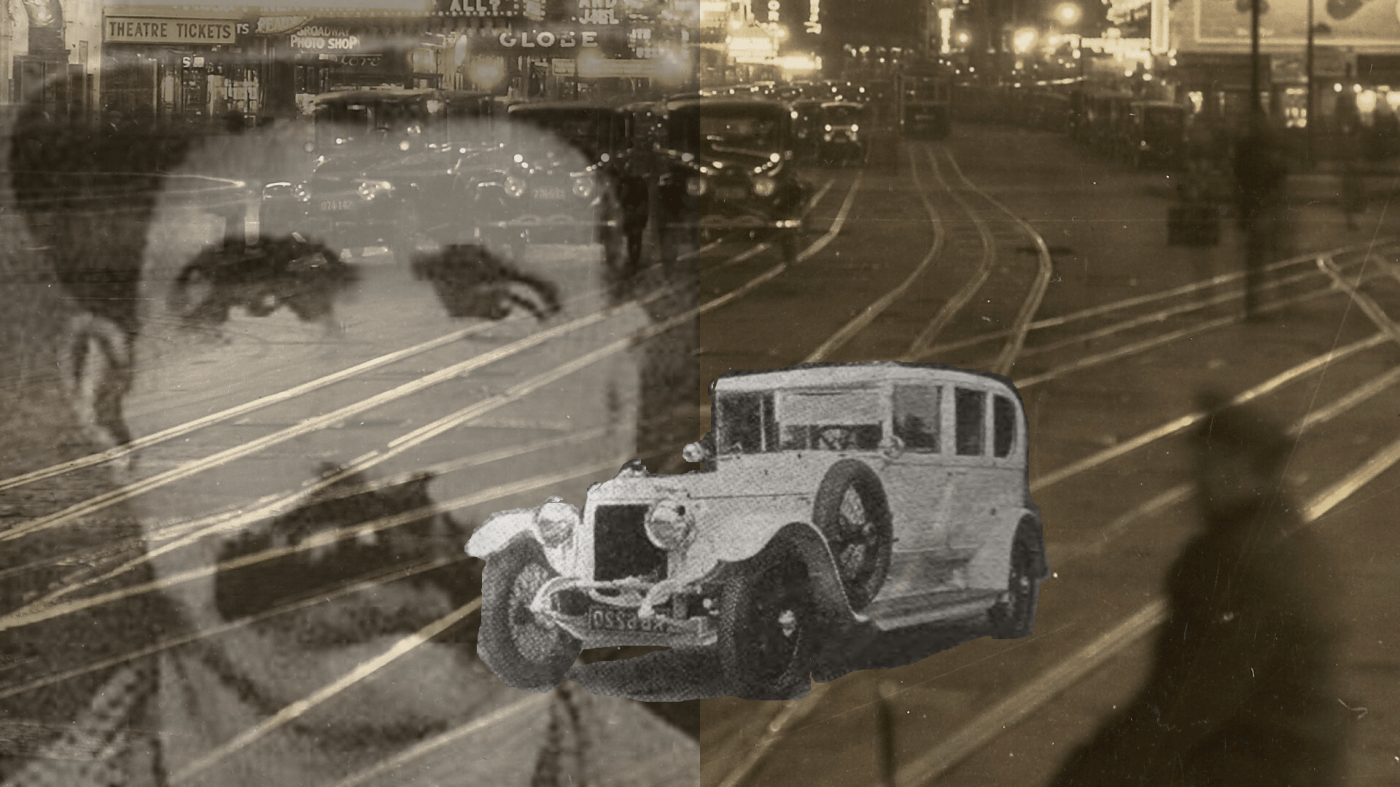

The wealthy Italian broker whose limousine Giuseppe Terranova drove had a long rap sheet going back to Sicily. Giovanni Pecoraro was among a who’s who of the Mafia rounded up after the assassination of the New York City police detective Joe Petrosino in Palermo in 1909. Pecoraro, who was the subject of a post here in January 2024, is one of those people who was seemingly everywhere in New York City’s early Mafia history. He may have even briefly led the Morello gang, before the Lo Monte brothers, when Morello and his counterfeiters were sent to prison in Atlanta. Pecoraro sacrificed everything for his deep involvement in the conflict between Morello and Salvatore D’Aquila.

Giovanni Pecoraro was born in Piana dei Greci and his wife, Vincenza Galati, was born in Partinico, like his driver. The Pecoraro and Terranova families were neighbors on First Street, between 61st and 62nd. In 1920, Giovanni’s wife and driver both told the census enumerator that they ran dry goods stores on the same block, around 60th Street and Second Avenue. It appears that they were talking about the same store. (The feed stores that his old boss Fortunato Lo Monte, and gangsters Angelo Gagliano and Joe DeMarco both ran, were in East Harlem: miles away on 108th Street.)

When Terranova was killed, police said they thought he was lured to his death by a woman for reasons to do with a liquor or gambling feud (Chauffeur lured to his death by woman is theory, 1921; Death of Giuseppe Terranova, 1921). That explanation roughly describes the war among Salvatore D’Aquila and his former fellows.

D’Aquila was more powerful than either of the factions who opposed him, but Morello had a large coalition that opposed D’Aquila’s domination of the rackets in New York (Dash, 2009, pp. 390-400). According to Mike Dash, Joe Masseria, an old associate of the Morello-Terranova Family, was now the second most powerful mafioso in New York City, and took on Morello as an advisor (Dash, 2009, pp. 423-25).

In resolving the question of what happened to Morello’s gang in these years, the question of when and with whom Gaetano Reina split from Morello is reopened. In the accounts centered on Reina, he left Morello’s gang around the same time as D’Aquila, around 1914: while Morello and Lupo were still in prison. However, the account that Mob Archeologists Angelo Santino and Eric Stonefelt have hammered out on the Black Hand forum describes a 1920 LoIacono loyalist group which is somehow the same predecessor to the Lucchese Family as Gaetano Reina’s.

In this version, Santino claims Reina didn’t split from the Morello-Terranova Family until after Morello’s release from prison in March 1920 (Question on the second NYC mafia war, 2023). In response to my request for more information, Stonefelt is more specific, saying the Morello Family split into what became the Genovese and Lucchese Families in 1923, with the Lucchese Family taking most of the corleonese faction, and the Genovese taking a large proportion of new recruits, many of them mainland Italians. Neither explains what happened to the LoIacono loyalists after his assassination: whether they dissolved back into the Morello Family membership and if so, how they were distributed in the 1923 split.

After the chauffeur was killed, the next target was Carmelo Nicolosi, a man of many professions: he was at different times a plasterer, barber, and baker. He employed narcotics smuggler Mariano Marsalisi as a barber in 1918 (Mariano Marsalisi draft registration, 1918). Like Morello, Marsalisi, and Lagumina, he had deep roots in their native Corleone, an attribute Morello valued in his close associates.

In April, Nicolosi was shot twice in the back, a couple blocks from home. He survived long enough to tell police that he had no enemies, and no idea who shot him (109 Murders in N.Y. in 1921, 1921; Warner et al, 2014).

A month later, Giuseppe Lagumina was killed. He was the manager of the Interborough Ice Cream Company from which someone shot at—though he missed—Giuseppe Terranova, the driver slain in January. Lagumina was carrying a large sum of money and wore expensive jewelry, but robbery wasn’t the motive: none of these items was taken (Man is killed by black handers, 1921). One of the suspects was “Diamond Joe” Viserte (Bootleg roundup follows slaying, 1921).

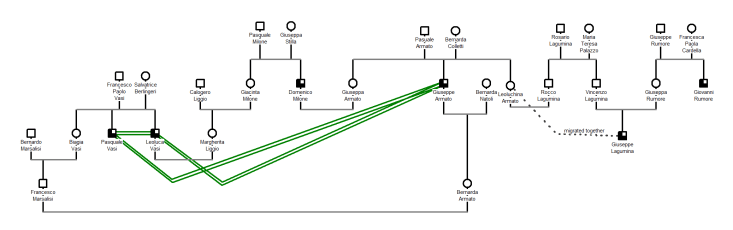

Corleone native Giuseppe Lagumina first arrived in the United States in 1905 with his aunt Leoluchina Armato and joined his uncle Giovanni Rumore, an important Morello gangster, in New York (Manifest of the SS Sicilia, 1905). Leoluchina met her brother, Giuseppe. Giuseppe Armato, the Vasi brothers, and Domenico Milone were among those found guilty of passing Giuseppe Morello’s counterfeit bills.

The January victim, Giuseppe Terranova, worked for Giovanni Pecoraro. Lagumina had a wide web of family ties to the Morello faction that survived his assassination. What connected these murders were the means to finance Morello’s war against D’Aquila. Through their criminal ties to Morello, Pecoraro, Nicolosi, and Lagumina entrusted their lives to the Morello-Terranova organization, and made a mortal enemy of D’Aquila.

That fall, Salvatore D’Aquila denounced Giuseppe Morello and Ignazio Lupo in a general assembly meeting and called for their deaths, forcing them to flee the country. Giovanni Pecoraro accompanied them with Ciro Terranova. Terranova, Morello, and Pecoraro returned to New York after D’Aquila rescinded the call for Morello and Lupo’s deaths, but the former leader of Morello’s gang, his younger half-brother Vincenzo Terranova, was killed the following spring. Joseph Masseria took over the gang, with Morello still serving as his consigliere. Pecoraro was killed by D’Aquila’s men in 1923, but Masseria’s protection kept Morello safe until the first rumblings of the Castellammarese War, in 1930.

Sources

Baptism of Joseph Terranova. (1893, April 2). Record no. 265. “Italia, Palermo, Diocesi di Monreale, Registri Parrocchiali, 1531-1998,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-YMF9-RBC?cc=2046915&wc=MG3S-L29%3A351041001%2C351041002%2C351477901 : 20 May 2014), Partinico > Maria Santissima Annunziata > Battesimi 1892-1894 > image 150 of 224; Archivio di Arcidiocesi di Palermo (Palermo ArchDiocese Archives, Palermo).

Bootleg roundup follows slaying; suspect trapped. (1921, October 15). Daily News (New York, NY). Pp. 1, 3. Newspapers.com.

Chauffeur lured to his death by woman is theory. (1921, January 27). The evening world. FultonHistory.com

Critchley, D. (2009). The origin of organized crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. Routledge.

Joe Tarranova petition for naturalization. (1920, May 3). “New York, U.S. District and Circuit Court Naturalization Records, 1824-1991,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9HD-GDVX?cc=2060123&wc=M5PH-162%3A351659901 : 31 May 2018), Petitions for naturalization and petition evidence 1920 vol 133, no 32901-33150 > image 675 of 842; citing NARA microfilm publication M1972, Southern District of New York Petitions for Naturalization, 1897-1944. Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685 – 2009, RG 21. National Archives at New York.

Joseph Terranova draft registration. (1917, June 5). “United States, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-81X3-4TJ?cc=1968530&wc=9FZB-HZ9%3A928312401%2C929042801 : 15 October 2019), New York > New York City no 131; I-Z > image 3480 of 4146; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Man is killed by black handers. (1921, May 17). The evening telegram (New York, NY). P. 2. FultonHistory.com.

Manifest of the SS Sicilia. (1905, October 12). Line 14. https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAyNDYzMTMwMDc0Ijs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7

Manifest of the SS Virginia. (1910, April 10). Line 2.

https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAzMjAwMDIwMDAyIjs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7

Mariano Marsalisi draft registration. (1918, September 12). “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-91N9-QJJ?cc=1968530&wc=9FZB-2NY%3A928312401%2C929062201 : 14 May 2014), New York > New York City no 160; Bellario, Concito-Z > image 3447 of 6043; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

The Mob Archeologists. (2023, February 23). Joe Masseria, Giuseppe Morello, & How the Genovese Family Formed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIbB4Q6x-f8

109 Murders in N.Y. In 1921; 59 Unsolved. (1921, June 13) New York Tribune. P. 1

Pecoraro household, Lines 21-22. “United States Census, 1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR6R-XGX?cc=1488411&wc=QZJ5-SLQ%3A1036473601%2C1039156701%2C1040159201%2C1589340171 : 12 September 2019), New York > New York > Manhattan Assembly District 14 > ED 987 > image 22 of 28; citing NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Question on the second NYC mafia war. (2023). The Black Hand Forum [Bulletin board].

https://theblackhand.club/forum/viewtopic.php?p=257594&hilit=Lagumina#p257594

Terranove household, lines 94-95. (1920, January 5). “United States, Census, 1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR6R-X25?cc=1488411&wc=QZJ5-S2P%3A1036473601%2C1039156701%2C1040159201%2C1589340238 : 12 September 2019), New York > New York > Manhattan Assembly District 14 > ED 988 > image 4 of 16; citing NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Warner, R., Santino, A., and Van ‘t Riet, L. (2014, May). The early New York mafia: an alternative theory. Informer Journal. Pp. 4+

Waugh, D. (2019). Vìnnitta: The birth of the Detroit Mafia. Lulu Publishing Services.

Leave a comment