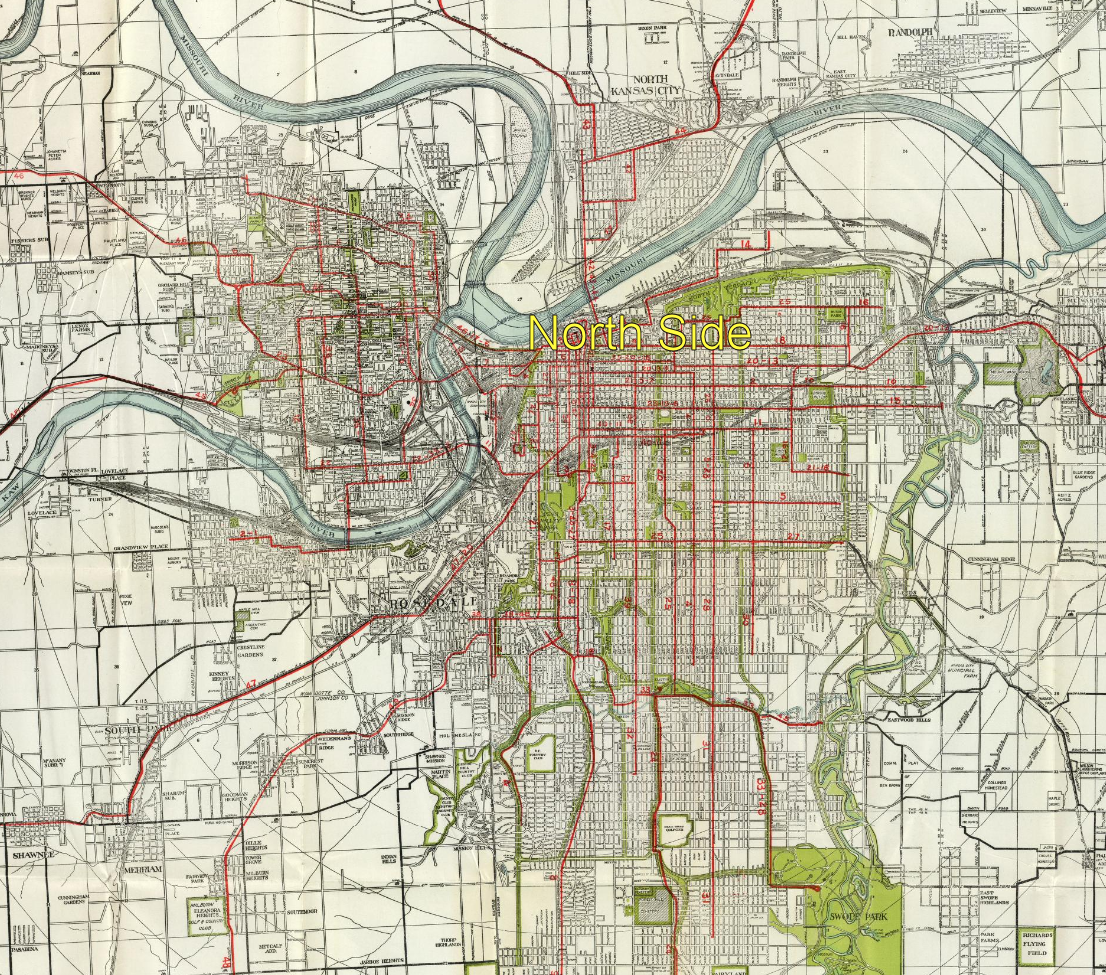

Beginning in the 1880s, Kansas City’s best-known and most populous “Little Italy” was in the neighborhood known as the North Side.

This 1920 Gallup map of Kansas City from the David Rumsey Map Collection shows the old North Side neighborhood, snugged up against the railway lines that run south of the Missouri River. Source: https://www.davidrumsey.com/maps870017-23955.html

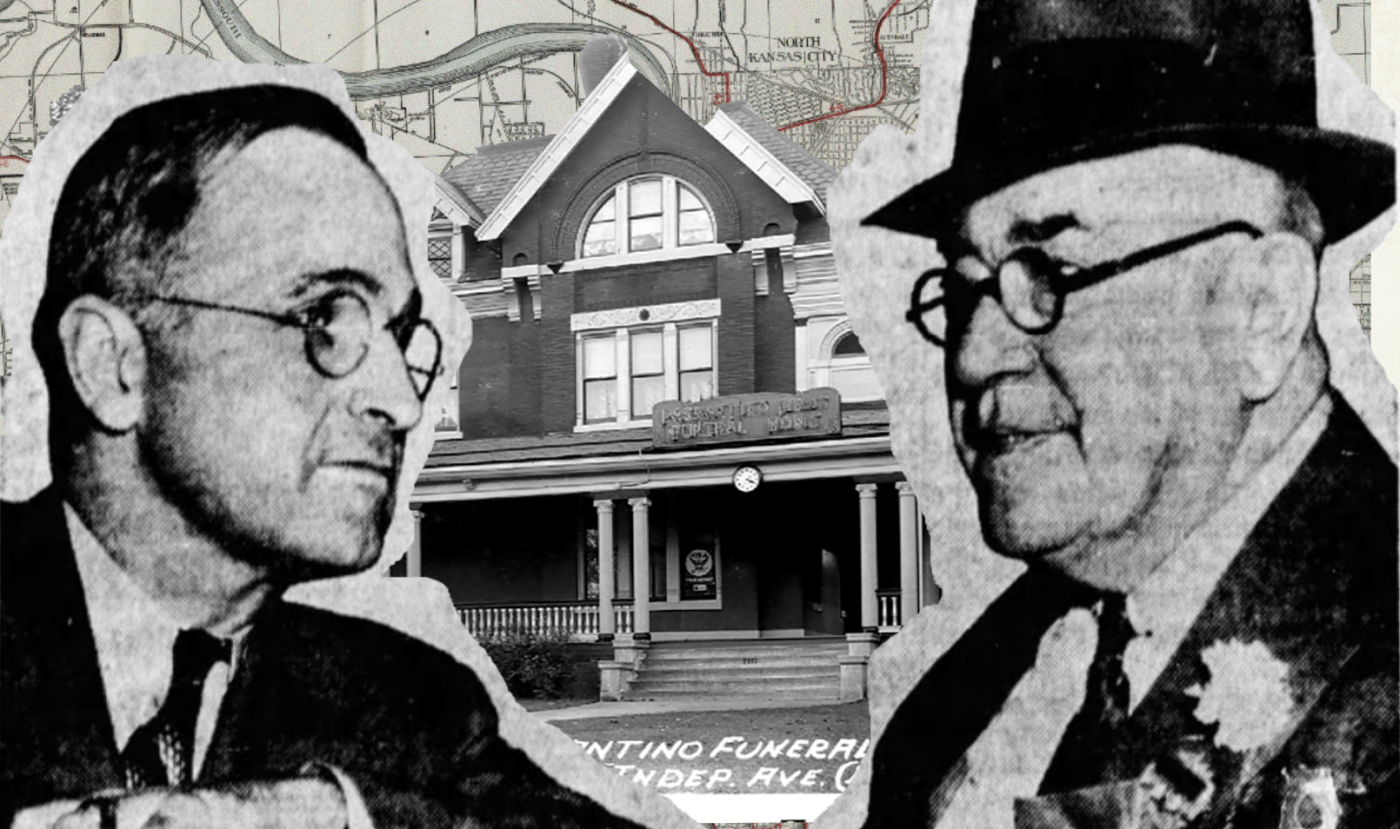

Ground zero of the Mafia going back to the Black Hand era, the North Side was an increasingly important part of T.J. Pendergast’s political power in Kansas City at the advent of Prohibition. (Pendergast is pictured, at right, in this post’s feature image. On the left is Harry S. Truman.) Naturalized Italian Americans voters turned out reliably for Pendergast’s candidates and voted as directed by their ward bosses—and the thugs they employed on election day.

Italian organized criminals in the vice trades operated quietly under Pendergast’s protection, but with the advent of Prohibition, the North Side’s criminal leadership class was becoming more ambitious. Serious bootleggers, among them the famed DiGiovanni brothers, sought monopolies to secure and protect their investments. They wanted direct control over the city resources that made the vice trades possible, like the police, which were doled out by Pendergast. In 1928, a small cadre of powerful Italians on the North Side chose the handsome, smooth-talking young thief turned politician, Johnny Lazia, as their front man.[1] Lazia overthrew his political mentor, Michael Ross, and forced Pendergast to reckon with the Italians directly.[2]

At the time Lazia was making his bid for political power, one of the best-known Italian families in the North Side were the Passantino brothers, who owned a large funeral home on Independence Blvd. The eldest of the brothers was Rosario “Rosie” Passantino. In addition to his role in the family business, Rosie was a security bondsman with a near-monopoly on bail bonds in Kansas City. Dead or alive, you could count on the Passantino brothers to take care of you.

Rosie Passantino got on my radar through the organic, circuitous route that describes my typical research pattern. While researching some families in the Bryan, Texas area (which led me to write The contract murder of Sam Degelia, Jr.), I learned about Nick Fazzino, aka Nick Quinn, an armed robber and early criminal associate of Charles Carrollo from the North Side, who was caught in Houston while on the run from murder charges.[3]

Learn more about the criminal and political career of Nick Fazzino on Patreon. Become a Mafia Genealogy Researcher ($10/month).

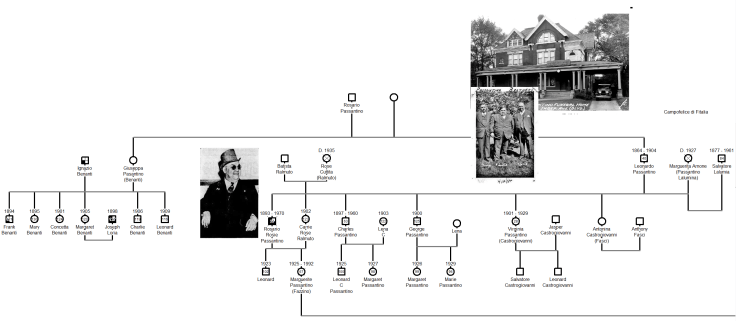

Nick Fazzino‘s son, Alex J. Fazzino married Rosie Passantino’s daughter, Marguerite, in 1946.[4] Alex was a bondsman who became a Missouri state House representative in 1969.

His father-in-law, Rosario “Rosie” Passantino was a Kansas City native and lifelong resident of the North Side. He grew up with his own parents and siblings, and the family of his father’s sister, Giuseppa, which included her husband, Ignazio Benanti, and their children. Their oldest child, Frank Benanti, was a year younger than Rosie, who was the oldest child in his family.

Rosie’s father, Leonardo Passantino died of diabetes when he was just 37, in 1904.[5] In those days, there were no effective treatments. Patients would starve despite eating. Food became poison. The first experiments with injected insulin were a miracle cure, but they were not performed for another fifteen years.

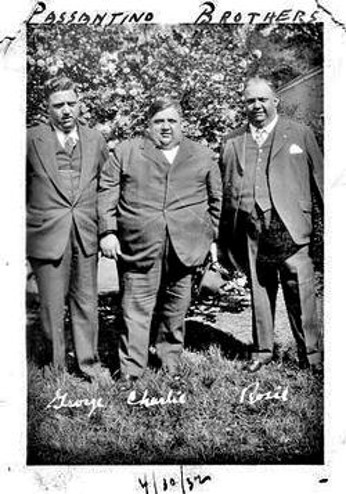

Photo: George, Charles, and Rosario Passantino

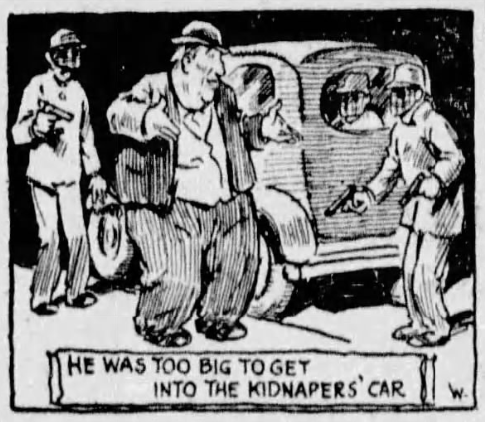

Rosie was ten when his father died. While Leonardo’s illness could have been the backstory behind the noteworthy size of two of his sons in adulthood— an unconscious attempt to undo or prevent the fate that came for their father—another, possibly tongue-in-cheek explanation for Rosie Passantino’s size was offered by The Kansas City Star in 1937.

In the form of an interview conducted by a new reporter of a veteran of the police beat, neither of them named, the Star made the claim—which may have been no more than a humorous jab at the formidable fat man, and not to be taken seriously—that before Rosie became a success, he had a job breaking in shoes damaged in a fire sale for a second-hand salesman. The work broke Passantino’s arches, giving him the flat-footed gait of “a steamboat trying to walk off a sandbar.”[6]

This characterization fit the Passantino brothers’ reputation as scrappy, self-made success stories. The Passantinos would become one of the wealthiest and most prominent Italian families in Kansas City. They came to own a great deal of real estate, several groceries, and saloons on the North Side. But in 1910, they were not yet prosperous.

When Leonardo Passantino was still alive, he and his brother-in-law were naturalized citizens, sharing a residence where they supported their young families on the pay of lowly day laborers. After Passantino’s death, Ignazio Benanti owned a grocery and a saloon.[7] His son, Frank, became an attorney and a Democratic ward boss.

Rosie’s mother remarried within a few years to Salvatore “Sam” Lalumina. Given the way his stepchildren cared for him in old age, and the obituaries written for him, they genuinely cared for Lalumina.[8] But not everyone in the family was happy following Marguerita’s remarriage. Six years after Leonardo Passantino died, Giuseppa and Ignazio Benanti sued the rest of the family—including Rosie and his siblings, who were still minors, their mother, Marguerita, and their mother’s new husband—which forced the sale of a piece of real estate at public auction.[9] The family feud must have been very stressful, given how close they had been for years.

Ignazio Benanti ran a saloon through the 1910s. He was arrested in 1915 with a dozen Italians who police investigated for Black Hand activity. At the time, reporting painted the Benantis as a wealthy, successful family: more resembling the target of extortion than its perpetrator. Ignazio’s son, Frank, the attorney, was able to get him out of jail quickly.[10]

Rosie Passantino claimed in a 1945 interview to have started his bail bonds business in 1915, when he was just 22 years old. The story he told was that he decided to change career paths, having formerly been a saloon keeper.[11] Like his uncle Ignazio Benanti, Rosie owned a saloon on East Sixth Street. Not yet married, he lived in his stepfather’s household, which was the only Italian family on a mostly Black street in the 1910 census.[12] They lived at number 217, the same address where Rosie had his saloon.[13]

Despite the draft and being called up for service in March 1918, Rosie was still in Kansas City when the board of public welfare heard evidence from the police commissioner that his saloon was the hottest rendezvous point for drug sales on the North Side.[14] It was this, in March 1918, that prompted Rosie Passantino’s exit from the industry. Sometime in the next twenty years, he made a savvy choice to enter what would become a booming business, serving his former colleagues when they got into trouble.

Rosie’s cousin made a similar choice to serve his criminal friends and neighbors: by providing legal counsel. The son of an Italian immigrant who could not read or write, Frank Benanti was educated: a lawyer in an era when that fact nearly always made it into print. He was rarely ever just a lawyer but an Italian lawyer.[15] As a member of the bar he was sworn to uphold the law, and as the son of a prominent family on the North Side, he represented a cohort’s respectability and dignity. But in his other guises, as a family man close to organized crime and deeply involved in the political machine, he wasn’t above using his influence.

Besides whatever he did to get his father out of jail, Frank Benanti lied about his sister’s age after her very public “elopement,” as the news euphemistically described the incident, at age thirteen.[16] The groom, Joseph Loria, was twenty-one, a neighbor on East Sixth Street, and active in an organized fencing ring.[17] Ignazio Benanti would not give his consent to the union. On Loria’s marriage license application, Frank signed his name, testifying that his younger sister, Margaret, was at least eighteen and legally old enough to marry without parental consent.[18]

During the Great War, as part of his political persona, Frank Benanti led a 100-man committee selling war savings stamps door-to-door.[19] But not long after the war’s end, he was charged as an accessory in two large-scale thefts. Benanti stood accused of buying both a load of shoes from a railroad car, and the loot from a robbery of the State Bank of Buhler in Kansas.[20] Two days after tens of thousands of dollars in stolen liberty bonds and stamps, identifiable by their serial numbers as having been stolen from the bank in Kansas, were found in Frank Benanti’s home, his father’s saloon at 401 East Sixth Street was closed by the excise clerk.[21]

Frank Benanti was taken into federal custody for fencing stolen goods in February 1919, to the protests of party leaders.[22] Agitating the political base to win the freedom of certain criminals was a common ploy by the North Side Democrats, one that culminated in the Union Station Massacre, in which armed criminals attempted the liberation of bank robber Frank “Jelly” Nash in the summer of 1933. Two federal agents, two police officers, and Nash were killed. John Lazia helped to hide the perpetrators by manipulating the investigation. Regardless, coverage of the massacre further cemented Kansas City’s reputation for municipal corruption.[23]

Rosie Passantino followed his cousin into local politics. He was the party clerk who signed off on a canvas of Benanti’s precinct in 1919, the veracity of which was questioned by Republican election commissioners, who accused them of ballot stuffing. Both men had to admit before the commissioners board that neither of them had made the canvas.[24]

After his saloon was closed by the board of public welfare, Rosie and his brothers Charles and George were employed as chauffeurs for a taxicab company.[25] A later biography of the Passantino brothers claims they owned their livery service, though this is not what they told the census enumerator in 1920. According to the biography, the brothers worked for another funeral home owner, Antonio Sebbeto, before opening their own in 1930.[26]

Livery—offering carriages and horses for rental, the predecessor of the taxicab business—was an industry that naturally flowed from providing funeral services. Sebbeto, or any other funeral home owner, might have rented livery out for public use when it wasn’t needed for a funeral. There is very little record of what the Passantinos were doing during the 1920s. That said, being in any kind of transportation business on the eve of Prohibition was potentially very lucrative and might have allowed the brothers to purchase a mansion together with their pooled earnings.

Rosario Passantino married Carrie Rose Ralmuta in the spring of 1920. They had two children, Leonard and Marguerite, who grew up with their cousins in the second and third floors of the funeral home at 2117 Independence.[27] Carrie, as the wife of a community leader, fulfilled her expected public role by serving on a variety of committees. In 1938, she was on the finance committee for the 7th annual convention of the National Italian-American Civil League with the wives of “Charlie the Wop” Carrollo and state House rep Frank Mazzuca, and gangsters Charles Gargotta, Peter DiGiovanni, and Thomas “Tano” Lococo.[28]

The Passantino brothers purchased the building that would serve as the family business headquarters in 1929.[29] It was home to all three brothers, their wives, and children, housing as many as fourteen members of the extended family at one time. Though it is no longer a residence, the Passantino Brothers Funeral Home is currently operated by a third generation from the original location.[30]

By the late 1920s, Rosie Passantino was already known as a bail bondsman, and he continued to be identified with this profession rather than the family business. As late as 1945, he was said to be living “above his brothers’ mortuary” on Independence.[31] The first time he was described in the news as one of the funeral home owners was in a 1950 article about a home invasion that Rosie thwarted. Even in this article, the first mention of his name is followed by the words “professional bondsman.”[32]

If his cousin, Frank, was singled out in the press as the “Italian attorney,” Rosie Passantino was most frequently characterized by his size. In the summer of 1927, in the first published account describing Passantino as a bail bondsman, The Kansas City Times reported on a fistfight between Passantino and his business partner, Albert DeMayo. The men were said to each weigh 250 pounds, which was uncommonly heavy among their peers.[33] (In the registration for the Great War, the average man weighed 142 pounds and stood 5’7”.[34] Rosario Passantino was 5’6”.[35]) In 1930, Passantino was reported to weigh 300 pounds.[36] Seven years later, deep into the Great Depression, he’d gained another seventy pounds.[37]

Passantino and his partners had a virtual monopoly in Kansas City, Missouri, on bail bonds under the vice-friendly police administration controlled by the Pendergast machine.[38] He had an office on North Main Street, and a desk inside the police headquarters near the booking desk.[39] When “machine control” of the police department ended in 1940, Passantino was banned from police headquarters.[40] His checks, which used to be accepted without question under the previous administration, were replaced with a safe full of cash in the rear of a drugstore across the street. This arrangement proved short lived, as the drugstore owner complained the bondsmen’s presence drove away the police trade.[41] Rosie eventually settled into an office next door to the drugstore on East Twelfth Street.[42]

As his star fell inside police headquarters, so did Rosie Passantino’s weight. In the 1942 draft registration he was down to 240, and he had lost another ten pounds when it was reported in 1943 that he was appealing a $2.25 traffic fine, a weight he held steady in 1945.[43]

Election fraud, which had been business as usual in Kansas City for more than a generation, finally rose to the attention of the US attorney general’s office, which investigated the previous year’s election in the summer of 1947.[44] Rosie Passantino fled to Dallas to avoid testifying, but he was found and flown back to Kansas City. Rosie told grand jury members how machine workers kept track of voters on election day. He admitted to having been a follower of Pendergast, and a member of the North Side Democratic Club, and to his more recent ties with a challenger organization, the East Side Democratic Club led by Alex Presta.[45]

Presta rose to power in 1959, but his influence waned when he supported two unsuccessful mayoral candidates in a row. He resigned as chairman of the First Ward Democratic Club in May 1963. Nick Fazzino was appointed to the committee to replace him.[46]

Passantino brought his son-in-law, Alex Fazzino, into the bail bonds business with him in 1959.[47] Alex’s father, Nick, followed suit. Nick Fazzino was called a bondsman when he collapsed on the job in the local courthouse in 1969. He died from what appeared to be an asthma attack.[48]

Rosie Passantino died in the local hospital in June 1970, at the age of 77.[49]

Following Alex Presta’s death in 1974, state representative Alex J. Fazzino succeeded the machine leader as Northeast Democratic Club president.[50] That Fazzino was a pay-to-play politician who did favors for gangsters was something of an open secret.[51] He admitted to accepting a bribe in 1983 to prevent more restrictive fireworks regulations legislation from passing.[52] Fazzino was found guilty of extorting the bribe, and sentenced to four years in prison and a $10,000 fine. He appealed, but the Eighth Circuit Court confirmed the conviction.[53]

Alex J. Fazzino was widowered in 1992.[54] He died in 2005 at age 82.[55]

Sources

[1] Says he tried to steal eggs. (1913, January 24). The Kansas City Times. P. 4; Robber suspect caught through finger prints on broken glass. (1916, April 19). The Kansas City Post. P. 1; Tom & Harry: The Boss and the President [Documentary excerpt]. (2014, September 24). Terence O’Malley [YouTube channel]. Accessed 2 December 2025 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n7vYYP2NUA8; The history of the Kansas City mob (2017). (2022, January 13). Originally presented on C-SPAN3 American History TV. Accessed on Mobfax [YouTube channel] at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVSRh3-xRtg; Hayde, F. R. (n.d.) Kansas City, MO. AmericanMafia.com [website]. Accessed 2 December 2025 at https://www.americanmafia.com/cities/kansas_city.html

[2] Ivey, M. F. (n.d.) John F. Lazia. The Pendergast Years. Digital History [Website]. Kansas City Public Library. Accessed 2 December 2025 at https://pendergastkc.org/articles/john-f-lazia

[3] Says he resembles bandit. (1922, May 2). The Kansas City Times. P. 3; Slaying suspect is hunted here. (1936, September 17). The Houston Post. P. 12.

[4] “Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G97J-NSWH?view=explore : Nov 22, 2025), image 2215 of 2470; Missouri. State Archives. Image Group Number: 007067139

[5] Deaths reported January 23. (1904, January 24). Kansas City Journal. P. 20.

[6] Facts and stuff, son. (1937, March 10). The Kansas City Star. P. 12.

[7] “Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RVD-N66?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 528 of 1236; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004972624; Up to federal officers. (1915, August 1). Kansas City Journal. P. 5.

[8] Lalumia [Obituary]. (1961, November 1). The Kansas City Times. P. 23.

[9] Legal notices. (1910, February 24). The Kansas City Post. P. 10.

[10] “Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RVD-N66?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 528 of 1236; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004972624; Up to federal officers. (1915, August 1). Kansas City Journal. P. 5.

[11] Joy in ‘legit’ status. (1945, October 29). The Kansas City Star. P. 3.

[12] “Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RVD-N66?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 528 of 1236; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004972624

[13] “United States, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YTZ-ZPR?cc=1968530&wc=9FW2-DPX%3A928313001%2C928639701 : 23 August 2019), Missouri > Kansas City no 5; F-Z > image 2623 of 4546; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

[14] Drug sales close a saloon. (1918, March 19). The Kansas City Times. P. 4; North Side saloon is ordered closed. (1918, March 19). The Kansas City Post. P. 5; Men in the June 24 call. (1918, June 11). The Kansas City Star. P. 7.

[15] The saloons still open. (1917, November 24). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[16] Chicago police halt elopement from K.C. (1918, April 4). The Kansas City Post. P. 1; Romance blasted at 13. (1918, April 4). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[17] $25,000 in loot. (1920, August 12). The Kansas City Post. P. 1; Efforts to break up burglars’ ring get new impetus. (1920, August 14). The Kansas City Post. P. 5.

[18] “Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G971-MV7W?view=explore : Nov 30, 2025), image 192 of 2412; Missouri. State Archives. Image Group Number: 007101798

[19] Fifth ward club stars W.S.S. drive. (1918, August 20). The Kansas City Post. P. 3.

[20] Release three in theft case. (1918, May 15). The Kansas City Times. P. 6; A thief ring protected? (1919, February 14). The Kansas City Star. P. 1; Trace stolen bonds here. (1919, February 14). The Kansas City Times. P. 2; Politics still in fight. (1919, February 15). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[21] Police held Frank Benanti. (1919, February 13). The Kansas City Star. P. 1; Sprang coup on gang. (1919, February 15). The Kansas City Times. P. 1.

[22] Police held Frank Benanti. (1919, February 13). The Kansas City Star. P. 1; Politics still in fight. (1919, February 15). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[23] Ivey, M. F. (n.d.) John F. Lazia. The Pendergast Years. Digital History [Website]. Kansas City Public Library. Accessed 2 December 2025 at https://pendergastkc.org/articles/john-f-lazia

[24] Politics still in fight. (1919, February 15). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[25] “Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RXQ-N2K?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 426 of 1113; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004966303

[26]Kansas City Italians. (2025, November 1). Kansas City Italians [Facebook]. Accessed 22 November 2025. https://www.facebook.com/KCItalians/posts/pfbid0NUEDgikwCYmro5qr9SArZaqxy2SP8sqm84ZJLhr8tc7MjfHik396nrwpUcP5VaNel

[27] “Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RHR-7Y3?view=explore : Nov 22, 2025), image 382 of 1089; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004951796

[28] Await convention in July. (1938, May 18). The Kansas City Star. P. 20.

[29] Bushnell, M. (2025, November 1). A lifetime of service. Originally published in Northeast News on 21 November 2001. Image shared in Kansas City Italians [Facebook]. Accessed 22 November 2025. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1159569336357168&set=pcb.1159580153022753

[30] Randall, E. (2010, November 3). Passantino Bros. marks 80 years in Northeast. Northeast News [Website]. Accessed 22 November 2025. https://northeastnews.net/pages/passantino-bros-marks-80-years-in-northeast/

[31] Joy in ‘legit’ status. (1945, October 29). The Kansas City Star. P. 3.

[32] Arrested prowler in chapel may have bond trouble, too. (1950, June 28). The Kansas City Star. P. 6.

[33] Bondsmen fight for business. (1927, August 3). The Kansas City Times. P. 13.

[34]Americans at war. (2024). The United States World War One Centennial Commission [Website]. https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/edu-home/edu-topics/588-americans-at-war.html

[35]“Lewis, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS9M-146H-F?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 981 of 1033; National Personnel Records Center (St. Louis, Missouri). Image Group Number: 101539626

[36] U.S. writ on “Bank of Rosie.” (1930, February 11). The Kansas City Times. P. 2.

[37] Facts and stuff, son. (1937, March 10). The Kansas City Star. P. 12.

[38] U.S. writ on “Bank of Rosie.” (1930, February 11). The Kansas City Times. P. 2.

[39] Facts and stuff, son. (1937, March 10). The Kansas City Star. P. 12.

[40] Cite 15 captains. (1940, March 19). The Kansas City Star. P. 6.

[41] Boot to the bondsmen. (1940, March 22). The Kansas City Times. P. 8.

[42] “Lewis, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS9M-146H-F?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 981 of 1033; National Personnel Records Center (St. Louis, Missouri). Image Group Number: 101539626

[43] “Lewis, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS9M-146H-F?view=explore : Nov 23, 2025), image 981 of 1033; National Personnel Records Center (St. Louis, Missouri). Image Group Number: 101539626; His turn to post bond. (1943, September 12). The Kansas City Star. P. 4; Tab on voters. (1947, September 1947). The Kansas City Times. P. 1.

[44] Await a jury report. (1947, August 29). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[45] Tab on voters. (1947, September 1947). The Kansas City Times. P. 1.

[46] Vote seen as no test of strength of factions. (1962, March 7). The Kansas City Star. P. 3; Alex Presta resigns. (1963, May 3). The Kansas City Star. Pp. 1, 2.

[47] Court case centers on use of word liberty. (1959, September 1). The Kansas City Star. Pp. 1, 2.

[48] Bondsman to hospital. (1969, November 21). The Kansas City Star. P. 5; Nick Fazzino [Obituary]. (1969, November 27). The Kansas City Times. P. 47.

[49] Rosario Passantino [Obituary]. (1970, June 4). The Kansas City Times. P. 23.

[50] Patterson, K. (1974, September 4). Fazzino named to Presta post. The Kansas City Times. P. 1.

[51] Fitzpatrick, J. C. (1980, May 10). Legislator’s brother and Missouri battle over tavern license. The Kansas City Times. P. 21.

[52] Fazzino sworn in as house member. (1969, March 19). The Kansas City Times. P. 9; FBI Dallas. (1968, June 5). Daily summary [Memo]. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/mlk/releases/2025/0721/44-dl-2649_sec_004_ser_551-660-part_2_of_9.pdf Img 47 of 50; Kuehl, C. (1984, January 17). Fazzino says he received campaign funds in cash. The Kansas City Star. Pp. 1, 6; Dalton, B. (1984, April 20). Fazzino projects 2 images as lawmaker. The Kansas City Star. Pp. 1, 5; Fazzino appeals conviction. (1984, September 10). The Kansas City Star. P. 1; United States of America, Appellee, v. Alex J. Fazzino, Appellant, 765 F.2d 125 (8th Cir. 1985). (1985, June 20). U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit – 765 F.2d 125 (8th Cir. 1985). Justia U.S. Law [website]. Accessed 3 December 2025 at https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/765/125/414631/

[53] Fazzino appeals conviction. (1984, September 10). The Kansas City Star. P. 1; United States of America, Appellee, v. Alex J. Fazzino, Appellant, 765 F.2d 125 (8th Cir. 1985). (1985, June 20). U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit – 765 F.2d 125 (8th Cir. 1985). Justia U.S. Law [website]. Accessed 3 December 2025 at https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/765/125/414631/

[54] Fazzino [Obituary]. (1992, July 14). The Kansas City Star. P. 75.

[55] Alex Fazzino obituary. (2005, July 30). Kansas City Star. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/kansascity/name/alex-fazzino-obituary?id=4294524

Great post, very informative.

I came across a Francesco Passantino b1877 in Sant’Elia, just east of Palermo, while researching San Francisco. Frank was arrested in 1913 for sending ‘black hand’ letters and was also arrested when Antonio Fodera killed someone in a car accident in 1915. Frank was living in Coyote (near San Jose) at the time. I believe Fodera was an early San Jose boss or high-ranking capo at the time.

I also came across a Joseph Passantino, 196 Chrystie Street, murdered 1921-08-10 on Grand Street. I was never able to find much on Joseph, including who his parents were, just that he was born around 1889.

Side note: Word press is awful to log into, because they ‘check’ whatever password I want to use against online ‘lists’ they have access to, and then block logging in if they find your password on the list. Since I am not buying anything, nor using this site for anything other than mafia comments, I find their security both onerous and intrusive.

LikeLike

Hi Tony, I didn’t know about the security check on WordPress. Sorry to hear that. I don’t know a solution other than to converse on another platform like Facebook or Patreon.

LikeLike

I tried to pursue your Sant’Elia lead for Leonardo Passantino, father of Rosie, but there are big gaps in the records in the 1860s and 1890s, when he was born and married. I’m going to need more clues to find him.

LikeLike