The DiGiovanni brothers got their start in New Orleans and Chicago before rising to the top tiers of organized crime in Kansas City, Missouri.

The story of how the Kansas City Mafia began isn’t part of our collective awareness of Mafia history. If you look for a simple, coherent narrative, what you’ll find is a series of disconnected facts about the gangsters who were mentioned—or testified at—the Senate hearings on organized crime in Kansas City, held a generation after Prohibition.

The main problems I have with this version of events are that it smashes the chronology together and skips everything that happened before Prohibition. The entire formation of the Mafia is distorted and skimmed over. Not only the very successful DiGiovanni brothers, but several of their worthy peers in Italian organized crime circles were already doing very well for themselves by the beginning of 1920. The history of the Mafia in Kansas City has an earlier starting point than Prohibition.

Screen shot of the Wikipedia article on the Kansas City crime family grabbed on 3 January 2026

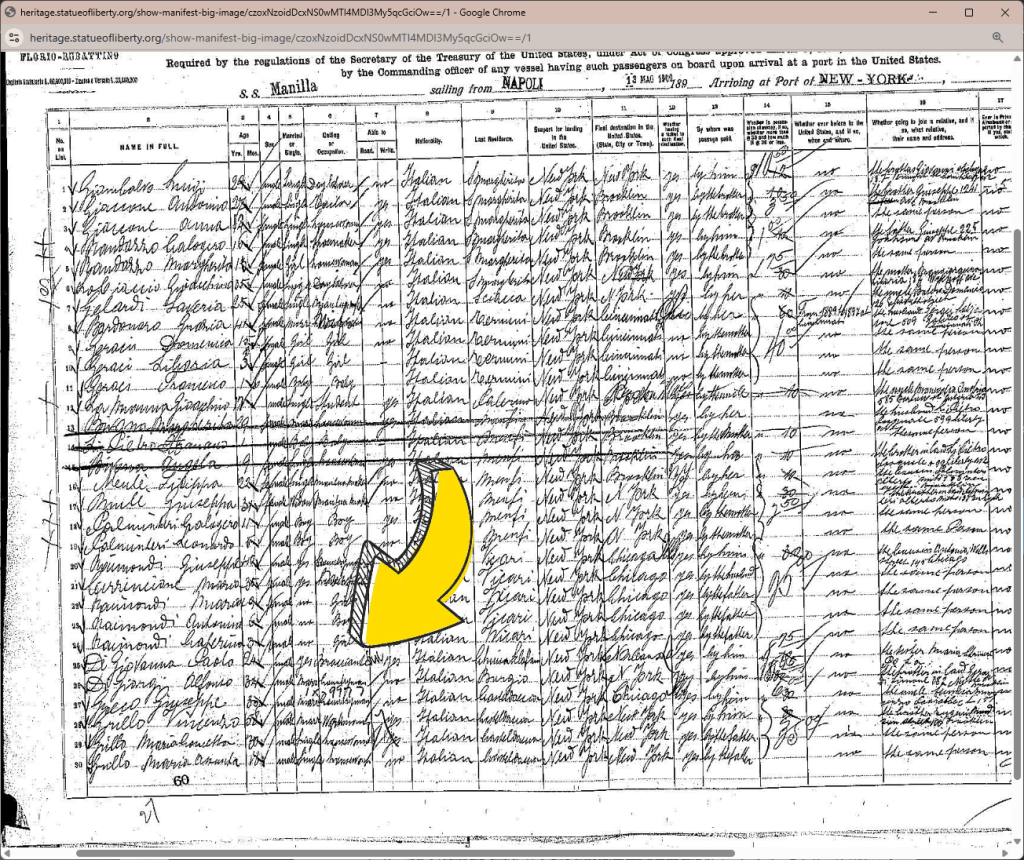

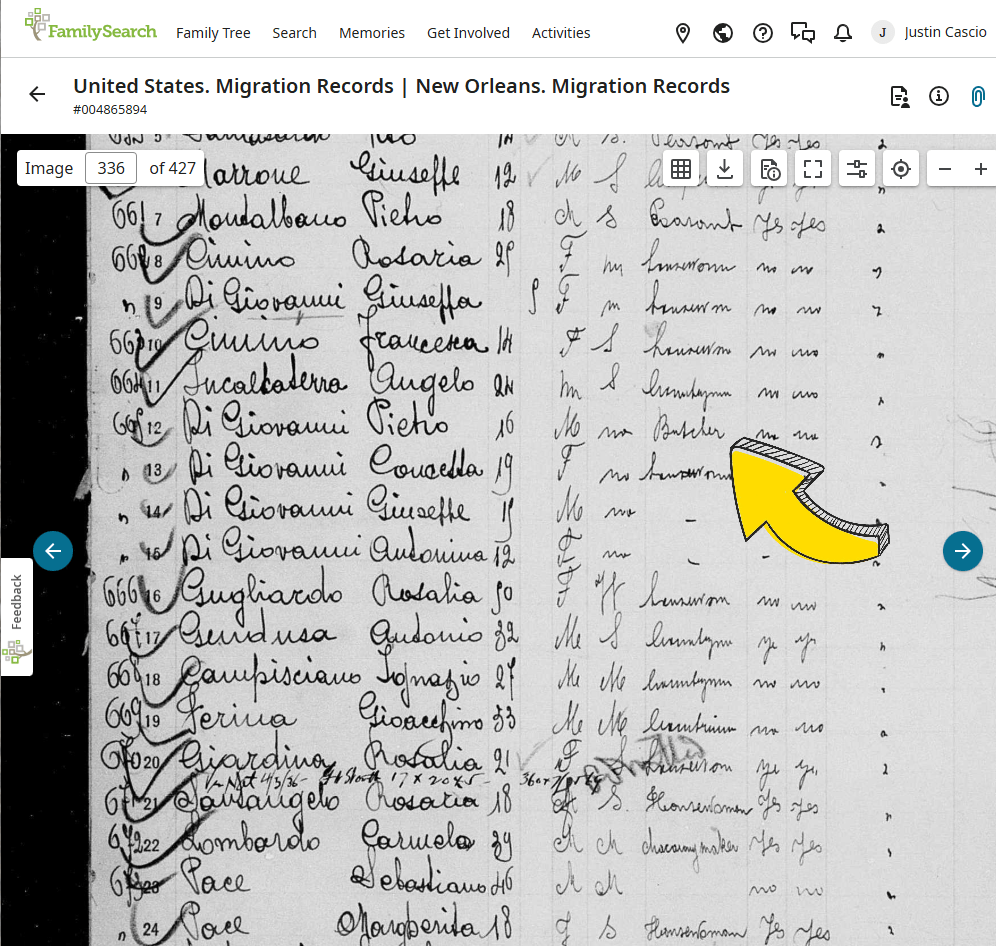

One “fact” I read about the DiGiovanni brothers when I was beginning my research was the unsourced claim that they fled Sicily as criminals in 1912. It’s not clear how this made it into the Kansas City Mafia Wikipedia page, but good secondary sources will confirm what I found: the brothers immigrated much earlier than 1912—between 1897 and 1903—joining their father and eldest sister in Louisiana.[1]

The Kansas City crime family got its power from the city’s political corruption. The Democratic party captured and maintained its power through blatant election fraud, a “tradition” they’d been carrying on for decades before any of the big names in the KC Mafia appeared on the scene. Plum jobs in the city administration were traded for bringing in the votes for “Big Jim” Pendergast (and later for his brother, Tom) and his slate of Democratic candidates.

In the first decade of the 20th Century Jim Pendergast tapped into the power of the organized Italian vote for the first time, as organized by resident padrone Joe Damico. After Damico was seriously injured and died in 1913, the contest for his throne was open. Whoever could connect the power of Little Italy to the corrupt base of power in Kansas City, and make himself most useful to the Pendergast machine, would be king.

Subscribers can read about King Damico of Kansas City on Patreon.

John Lazia would eventually wear that crown, supplying the Italian vote in exchange for concessions. Lazia’s constituency weren’t the residents of Little Italy, however, but its wealthiest organized criminals.

Lazia rose to his position through the criminal ranks, beginning as a lowly pickpocket. In 1915, the future front man for the Kansas City Mafia was a teenage thief, part of a gang led by “Black Mike” McGovern.[2]

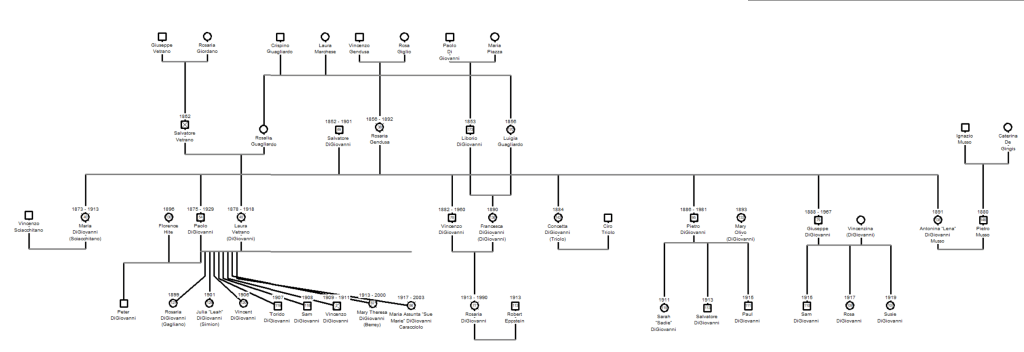

The DiGiovanni family were from Chiusa Sclafani, in the Palermo province of Sicily. The father, Salvatore, was a day laborer turned butcher, perfectly describing the rising middle class position of a mafioso of 1870s Sicily.[3] Salvatore taught his sons this new trade and they carried it on after migration to the United States.

In Italian records, Paolo retained his father’s occupational status as reported at his birth. Here he is in 1900 immigrating through the port of New York. Despite being the son of a butcher, he is called a bracciante (a day laborer).

Pietro DiGiovanni was called a butcher when he was sixteen years old and emigrating from Sicily with his sisters and brother. Giuseppe DiGiovanni, a year younger, is still considered a child and therefore has no profession.

The DiGiovanni brothers’ eldest sister, Maria DiGiovanni Sciacchitano (1873-1913), was the brothers’ destination contact in New Orleans. The oldest brother was Paolo (1875-1929), followed by Vincenzo (1882-1960), sister Concetta (b. 1884), Peter (1886-1967), Giuseppe/Joe (1888-1967), and the youngest, Antonina, called Lena, born in 1891.

Of the brothers, Vincenzo was the first to immigrate, then Paolo. Giuseppe and Pietro came together with two of their sisters in 1903.

Maria Sciacchitano remained in New Orleans. I lose track of the patriarch, Salvatore, after his family meets him in Kenner, Louisiana, in 1903. (Although for a few thrilling hours I thought he might be the mafioso and 1901 Chicago murder victim of the same name.) The rest of the DiGiovanni family moved over the next few years to addresses on Chicago’s Near North Side, in a “Little Sicily” run by the mafioso Mariano Zagone. Paolo and his wife were in Chicago by 1906, the year he became a naturalized citizen.[4] The brothers’ paternal uncle Liborio DiGiovanni and his family joined them in Chicago the same year.[5] Vincenzo, the second son of Salvatore DiGiovanni, married his first cousin, Francesca, daughter of Liborio, in 1911.[6]

Eldest brother Paolo DiGiovanni had a butcher shop in Chicago in the 1910 census. A year later, while his family still lived in Chicago, he was caught 500 miles away in Kansas City, selling wine without a license.[7] When Paolo’s future business partner, Joseph Berbiglia, applied for a license to operate a saloon at the same location, it was blocked due to protests from the nearby Holy Rosary Catholic school and church.[8]

Peter DiGiovanni, left, and Joe DiGiovanni (1979). Fun fact: with the exception of Joe, the DiGiovanni brothers were blue-eyed, and Paolo had blond hair.

In July 1915, youngest brother Joe DiGiovanni was arrested at brother Pietro’s grocery at 1002 Pacific Street as a suspected member of a Black Hand gang.[9] Bill Ouseley writes in Open City that Joe and another grocer, Paul Catanzaro, were both targeted by the Black Hand before being accused of extortion.[10] (I haven’t found any other evidence of this.)

A Kansas City police detective investigating the criminal conspiracy described the gang’s methods, in which members from multiple locations collaborated by sending their own arsonists and murderers to other cities in a kind of felon exchange program. The out of towners were used by local Black Handers in other cities to dole out consequences to victims who hadn’t paid the demanded fees.[11] Among the dozen suspects turned over to federal investigators that summer from Kansas City was Ignazio Benanti, the uncle of Rosie Passantino (who was the subject of last month’s story).[12]

Joe and his wife, Vincenzina, who married the previous fall, had their first child that October.[13] A couple of years later, he was seriously burned on his face and hands.[14] His injuries, which got him the nickname “Scarface Joe,” first appear in the public record when he and his brother registered for the draft in the summer 1917. Joe was a butcher who claimed to be unemployed because of his physical injuries, and asked to be exempted from the draft.[15] Peter DiGiovanni, a self-employed grocer registering on the fifth of June, claimed to be supporting his wife, three children, and a “crippled brother.”[16]

Scarface Joe’s burns were widely rumored to have resulted from the explosion of distillation equipment. He claimed they were sustained in a gas meter explosion: at least, that is what he says during the Kefauver hearings; Ouseley says he blamed them on an oil heater.[17] Based on what he told the draft board in 1917, it seems Joe’s injuries might have been fairly fresh, perhaps incurred that same year.

It was at around this time that the DiGiovanni brothers got their introduction to the black market in sugar. During the first World War, sugar was rationed, and the brothers, who were all in the grocery business, allegedly became black market dealers. After the war, they had a lot of sugar that was no longer subject to the rationing which had made it a hot commodity.[18] One of the stories which alleged the source of Joe’s scars was that he was burned setting a warehouse full of sugar on fire.[19] But sugar was about to become highly controlled and very valuable for another reason, one the brothers could have foreseen at war’s end.

By 1918 the Digiovanni Brothers had two locations in Kansas City, Paolo’s original location at 548 Campbell—where he was arrested for the unlicensed sale of wine in 1911—and Pietro’s at 1030 E. 5th Street.[20] That year on the ninth of October, Joe DiGiovanni shot two women who were shopping in the store he owned with his brother, Pete. One of the women was killed and the other, her teenage daughter, was seriously injured.[21] The brothers were briefly held but there was no further news of the shooting, which suggests it was not prosecuted.[22]

A week later, on 17 October, Paolo’s wife, Laura died.[23] Laura Vetrano DiGiovanni may have always been Paolo’s common-law wife. I’ve found no record of their marriage in the United States or in their native Chiusa Sclafani, where their eldest daughter was born.[24]

Joe DiGiovanni and Jim Balestrere were recognized as the two biggest bootleggers in Kansas City at the beginning of Prohibition.[25] Balestrere was better known as an arbitrator, a padrone in the style of Joe Damico, who helped his immigrant neighbors resolve their differences with one another and the legal system.[26] In the first year of Prohibition, Paul DiGiovanni’s store was hit twice by federal raids, in May and October, the second time resulting in the arrests of both Paul and his brother, Joe.[27]

Vincent Chiapetta was partnered with Pete, Vincent, and Joe DiGiovanni in a sugar house on Fifth Street. Chiapetta, a friend of Nicola Gentile who enjoyed the mafioso’s protection, was later a partner in a wholesale grocery at 516 E. Fifth St, a business Gentile left him when he returned to Sicily in 1925. There were at least three other big sugar houses in the area, the largest run by the Carrollos.

In 1922, Paul DiGiovanni had another grocery location at 712 Walnut which he operated in partnership with Joseph Berbiglia. One night after closing, Paul and his partner were robbed on the street by three masked bandits who fled in a waiting car. The grocery business had been treating Paul DiGiovanni very well, indeed, because the robbers made off with nearly $7,000 worth of diamond jewelry which Paul had been wearing: a value of about $134,000 today with inflation.[28]

The following year, Paul sold two commercial buildings and purchased a new family home at 444 Benton Blvd.[29] His brother, Joe, became a naturalized citizen.[30] In the summer of 1924 Paul remarried to Florence “Flora” Hite.[31] He died from natural causes at age 54 on 27 August 1929.[32]

Sometime in the late 1920s, Ouseley writes, Joe DiGiovanni approached the Carrollos about consolidating the sugar houses in Little Italy. Their new syndicate created a monopoly in the black market on sugar and distillation supplies.[33] Their involvement in the transportation end, when automobiles were still overtaking horses, was also complete, making it difficult to procure or finance a car without paying a “tax” to Joe DiGiovanni.

Joe controlled payouts to the Kansas City police. With police protection taken care of, the underworld in Kansas City had only the problems of success with which to contend. Bootleggers and other vice leaders learned quickly how to operate a rapidly growing business, or were made irrelevant by someone who would. The lessons learned were transferable to the growing traffic in narcotics that flowed through Kansas City.

John Lazia had made himself indispensable to Tom Pendergast. Having built up his own loyal voting bloc, Lazia turned on the machine in the 1928 election and made Pendergast dance to his tune. What changed between the old “King” Damico and Lazia was more than a matter of style. Lazia created a new political club and the players came to him. In addition to taking power formerly reserved for Pendergast, Lazia was recognized as the public leader of the DiGiovanni brothers’ criminal syndicate, and the protector of Italian organized crime.

John Lazia

Lazia’s role vis a vis powerful men like Jim Balestrere and Joe DiGiovanni is still debated. The most popular view is that he was placed in his public-facing role by the older gangsters, who were uncomfortable with the requirements of the position: not all of the brothers were citizens, nor were they all able to read and write. Knowledgeable sources indicated to Ouseley that Lazia was never an inducted member of the Mafia and that Lazia paid for the privilege to operate. Whether he paid to play or was induced to perform his part by the true Mafia, his public leadership undoubtedly benefitted the Sugar House syndicate.

Lazia, as previously mentioned, began his career as a petty criminal. He worked his way up to the defendant of a landmark fingerprint case in two robberies. As he climbed the political ladder, he retained and developed his own gang of toughs, men he’d brought with him from the streets. After his death in 1934, these men merged into the outfit run by DiGiovanni and Balestrere.[34]

In the 1930 census, brothers Peter and Vincent DiGiovanni both headed families at 502 Campbell Street and told the census enumerator they were grocery store proprietors.[35] Which they were: groceries made excellent fronts for wine and liquor as well as wholesale sugar sales.

When Prohibition ended, the former bootleggers had new, legal distribution businesses up and operating, with freshly signed contracts to transport and sell alcohol. Joe and Pete DiGiovanni formed Midwest Distributing with Joe Spallo, and got an exclusive contract to distribute Seagrams. Chiapetta became a partner in Superior Wine & Liquor with Vincent DiGiovanni and distributed Schenley products. Tom Pendergast got the rights to distribute Anheuser-Busch through his beverage companies. In combination, this small cadre of organized criminals locked up the most important alcohol distributorships from the moment Prohibition was repealed.[36]

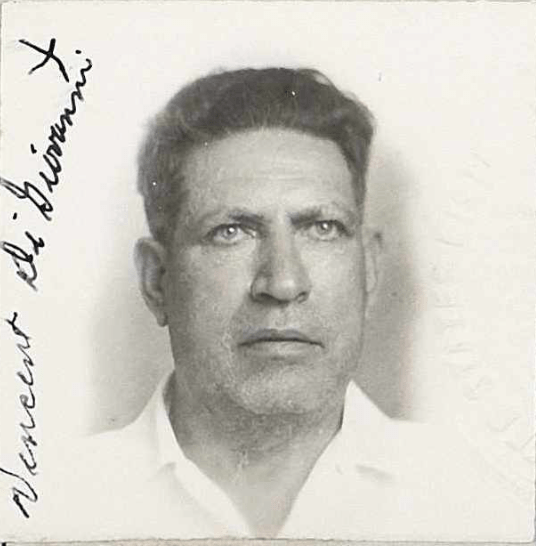

In 1940, Vincent DiGiovanni was the proprietor of a wholesale liquor company.[37] He declared his intention to naturalize the following year. He signed this document by making a cross.[38] During World War II, Joe and Pete DiGiovanni got into trouble with the OPA. In 1950, Joe DiGiovanni appeared before the Kefauver committee. Based on his testimony, his brothers were charged with price fixing and lost their license to distribute.[39]

Vincent DiGiovanni’s photograph and his mark, a cross, as they appeared on the declaration of intention to naturalize he filed in December 1941. Vincent had blue eyes like two of his brothers, Paul and Pete.

Joe DiGiovanni and Jim Balestrere led the most important crime syndicate through Prohibition and continued their success after its repeal. Men who had come up with Lazia—Tom Lococo, Tony Gizzo, Charles Gargotta, and Charles Binaggio—joined them in the upper ranks, and along with Balestrere came to be called the Five Iron Men in control of the Kansas City Mafia.[40]

[1] Vzo. Di Giovanni on the Victoria. (1897, October 30). Line 21. https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiNjAyNzQ1MDYwMDgwIjs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7; Manifest of the Manila. (1900, May 31). Line 25. https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiNjA1MTY0MDMwMDU1Ijs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7; “New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-95C6-SQP?view=explore : Dec 3, 2025), image 336 of 427; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004865894

[2] Robber suspect caught through finger prints on broken glass. (1916, April 19). The Kansas City Post. P. 1; Release an accused robber. (1916, April 20). The Kansas City Star. P. 1.

[3] Compare the 1875 birth of Paolo, in which Salvatore is a bracciale, a day laborer, to a record from 1882 of the birth of Vincenzo, in which Salvatore was reportedly a butcher. Atto di nascita, Paolo DiGiovanni. (1875, April 16). Record no. 62. Archivio di Stato di Palermo > Stato civile italiano (registri dei Comuni) > Chiusa Sclafani > Registro 14 > Nati https://antenati.cultura.gov.it/ark:/12657/an_ua36082394/0n3jPan Img 43 of 164; Atto di nascita, Vincenzo DiGiovanni. (1882, February 19). Record no. 46. Archivio di Stato di Palermo > Stato civile italiano (registri dei Comuni) > Chiusa Sclafani > Registro 21 > Nati https://antenati.cultura.gov.it/ark:/12657/an_ua36078460/wXd2yk3 Img 33 of 202

[4] “United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939N-JFWF-3?view=explore : Dec 1, 2025), image 2625 of 6793; Federal Archives and Records Center (Chicago, Ill.). Image Group Number: 004640985

[5] “Italia, Palermo, Stato Civile (Archivio di Stato), 1820-1947”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6NPM-8RLG : Thu May 29 19:58:19 UTC 2025), Entry for Liborio di Giovanni and Paolo di Giovanni, 3 May 1879; Manifest of the Konig Albert. (1906, September 27). Lines 22-26. https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiODAwMTUyMDgwMDM0Ijs=/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7

[6] “St. Philip Benizi, Chicago, Cook, Illinois, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-DZW9-MZL?view=explore : Jan 1, 2026), image 101 of 199; Catholic Archives and Records Center (Chicago, Illinois). Image Group Number: 004284716

[7] Catholics keep out a saloon. (1911, February 24).The Kansas City Times. P. 9.

[8] “Illinois, Cook County Deaths, 1871-1998”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N7JD-4BJ : Sat Oct 11 10:37:29 UTC 2025), Entry for Vincenzo Digiovanni and Paulo Digiovanni, 18 Jul 1911.

[9] Get three more of gang. (1915, July 29). The Kansas City Times. P. 15; 15 Italians tell police of paying large sums to Kansas City blackhand. (1915, July 30). The Kansas City Post. Pp. 1, 8; “Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYT6-9Q53?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 5484 of 5727; United States. National Archives and Records Administration,United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Atlanta Branch. Image Group Number: 005151863

[10] Ouseley, W. (2008). Open city: true story of the KC crime family 1900-1950. Leathers Publishing. Print. P. 45.

[11] ‘Stool pigeon’ was used to uncover blackhand. (1915, July 30). The Kansas City Post. P. 8.

[12] Up to federal officers. (1915, August 1). Kansas City Journal. P. 5.

[13] Births. (1915, October 7). The Kansas City Post. P. 10; “Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3D6-Y3VH?view=explore : Dec 3, 2025), image 454 of 563. Image Group Number: 106827342

[14] Investigation of organized crime in interstate commerce. (1950, July-September). Special committee to investigate organized crime in interstate commerce. United States Senate. https://archive.org/stream/investigationofo04unit/investigationofo04unit_djvu.txt

[15] “Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YT6-93FM?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 5482 of 5727; United States. National Archives and Records Administration,United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Atlanta Branch. Image Group Number: 005151863

[16] “Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GYT6-9Q53?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 5484 of 5727; United States. National Archives and Records Administration,United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Atlanta Branch. Image Group Number: 005151863

[17] Ouseley (2008), p. 70.

[18] Ouseley, W. (2008). Pp. 69-70.

[19] Ouseley, W. (2008). Pp. 69-70.

[20] Advertisement. (1918, January 31). The Kansas City Times. P. 6.

[21] Woman killed in quarrel. (1918, October 10). Kansas City Journal. P. 5.

[22] Two negro women shot. (1918, October 12). The Kansas City Sun. P. 1.

[23] Bigiuvanna [Deaths in Kansas City]. (1918, October 17). The Kansas City Times. P. 7.

[24] Atto di nascita, Rosaria Di Giovanni. (1899, October 27). Record no. 201. Archivio di Stato di Palermo > Stato civile italiano (registri dei Comuni) > Chiusa Sclafani > Registro 38 > Nati https://antenati.cultura.gov.it/ark:/12657/an_ua36078466/5gkbZaK Img 136 of 182

[25] Ouseley, W. (2008). P. 67.

[26] Ouseley, W. (2008). P. 67.

[27] Admitted a booze charge. (1920, May 28). The Kansas City Times. P. 2; Two plead guilty after seizure of big store of booze. (1920, October 25). The Kansas City Post. P. 1.

[28] Closed store, met bandits. (1922, April 16). The Kansas City Star. P. 2; CPI Inflation Calculator accessed 3 January 2026 at https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

[29] Two business properties sold. (1923, March 18). The Kansas City Star. P. 80; Home and homesite sales. (1923, August 12). The Kansas City Star. P. 62.

[30] “Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V3D6-Y3VH?view=explore : Dec 3, 2025), image 454 of 563; . Image Group Number: 106827342

[31] “Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9W7-5WS8?view=explore : Dec 1, 2025), image 1643 of 2543; Missouri. State Archives. Image Group Number: 007118675

[32] Death of Paul Di Giovanni. (1929, August 29). The Kansas City Times. P. 16.

[33] Ouseley (2008), Pp. 75-77.

[34] Ouseley (2008), P. 103.

[35] “Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRCM-FLS?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 340 of 1144; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 004951781

[36] Ouseley (2008), Pp. 166-168.

[37] “Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9MB-YL89?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 225 of 727; United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Image Group Number: 005460108

[38] “Kansas City, Jackson, Missouri, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-J36H-C9H5-X?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 166 of 187; United States. National Archives and Records Administration (Kansas City, Missouri). Image Group Number: 106890846

[39] Ouseley (2008), Pp. 176-177.

[40] Hayes, D. (1993, September 15). Reputed ‘iron man’ of KC mob is dead. The Kansas City Star. P. 61; May, A. (2009, October 15). The history of the Kansas City family. Crime Magazine. Accessed 27 December 2025 at https://www.crimemagazine.com/history-kansas-city-family

Leave a comment