When I started this blog, I told one of the earliest anecdotes I had about my family: a story about olive oil. My father’s paternal grandparents, Louis Cascio and Lucia Soldano, immigrated as teenagers with their families and settled in East Harlem, on 106th Street. After they married, Lucia and her youngest brother, Tony, sold olive oil to their neighbors, produced and exported by Louis’ brother-in-law.

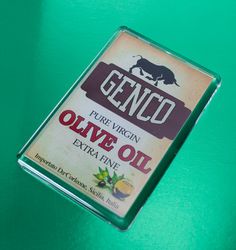

In my first post, I was doubtful that this story was true, or at least that it was the whole story, and not a cover for some other, hidden events. Was it even remotely possible that the olive oil story was the extra-virgin truth, as it was told to me? If so, why did it smell like a second pressing of “The Godfather”?

The farmland around Corleone, in the 19th century, was used according to its distance from the city: closest to town were the household gardens, surrounded by vineyards and orchards, and then land used alternately for pasturage and to grow grain. In Corleone there was an outer ring of almost-feudal lands, called contrada (lands) or “feudi,” fief holds, based on the original Roman farms. Many are still in existence, if diminished; the locals can tell you where they once were.

The smallest of these traditional holdings in Corleone, around 1800, were five salmi, or about 8.75 hectares, in size. Many small landowners owned far less than this, with a bit of land in one contrada and another, some in vines, some in trees. Most farmers in Corleone did not own any property at all, not even their houses.

A five salmi olive orchard could theoretically produce 39,000 kg of olives, if all of the trees were mature and healthy, and it was a favorable year for the olive harvest. That’s enough to keep 288 Italians in olive oil for a year, at today’s consumption rates. However, olives are a tough crop to rely upon, as a farmer. The trees tend to yield a good crop only in alternate years, like apple trees. They mature slowly, and do not produce saleable fruit for about ten years. But they can live for more than a thousand years.

Olive trees are extremely hardy and will usually recover from droughts and freezes. Growing anything here is tricky. Corleone is at 600 meters above sea level, where trees can sustain frost damage, and the land is dry for most of the year. The regulating agency governing olives in the Val di Mazzara, in which Corleone is located, limits olive production to no more than 8,000 kg per hectare. If the land is fully planted in the traditional way, with 28 feet between trees, that comes to around three and a third kilograms of olives per tree. This is well below the standards of ten or even fifty kilograms from a mature tree, reported by growers in other parts of the world.

Every olive producing region in Europe has its own varieties, very few of which have been transplanted to the New World. Three types of olives are grown near Corleone, all for oil production: Biancolilla, Nocelara de Belice, and Cerasuola. Sicilian olive oils are usually a strong shade of green, with a golden undertone, good body, and a complexity of flavor. Traditionally, olives are harvested by hand or with nets. The fruit is slowly milled on a trappeto, which keeps the paste unheated, and then the olive paste is pressed in a frantoio to release the oil. Extra virgin olive oil is still produced using a very similar process.

When my twice great-aunt Biagia Cascio was born in Corleone in 1884, olive oil was likely regarded as a precious commodity. The future olive oil exporter was born at number 3, via Banditore, in the northern part of Corleone, the second child of Giuseppe Cascio and Angela Grizzaffi. They lived in the “Upper Area” of Corleone, above via Roma, in what is called the Borgo in old records: the suburbs. North of the suburbs is a great open area. To the east of this address is a via Trappeto. There must have been at least two olive mills in town, possibly at different times. There is another trappeto that appears in Church censuses of the older, southern part of the city, early in the century.

Giuseppe Cascio was a farmer who suffered poor health, and died in 1899, when Biagia was fourteen. Her mother, older sister, and three of her younger siblings immigrated two years later, leaving her and her two youngest siblings in Corleone. I don’t know where they all lived, but it is likely they stayed with Angela’s brother, Leoluca. By this time, Leoluca and Angela’s parents had died, and Leoluca most likely inherited property from their father.

Angela, a young widow, and her older children joined her sister’s family in East Harlem. Two years later, her brother, Leoluca, brought Angela’s two youngest children with him to New York. Only Biagia did not immigrate. She married a man with the same name as her father—Giuseppe Cascio, her first cousin—in 1902.

Giuseppe was from a Mafia family. His godfather is also his namesake and maternal grandfather, Giuseppe Morello. His older cousin was the infamous gangster of the same name, named after the same grandfather. Giuseppe’s sister, Giovanna, married Pietro Majuri in 1897. Pietro was active in the Mafia in Corleone around 1900, under Giuseppe Battaglia. Two of their sons were active in 1962, under Luciano Leggio.

Biagia’s brother Louis and his wife, Lucia, my great-grandparents, married in New York in 1918. Immigrants made more money in New York than they did back in Sicily, and wanted the luxury goods they could now afford. Census records tell us that Louis worked in a laundry in 1920 and 1930. Even humble peasants from Corleone would, of course, know quality when it came to olive oil, and I expect many preferred the distinctive flavor of oil produced in their hometown, where they knew its provenance and production method, and it tasted like home.

Long before the Mediterranean diet swept the United States, Ciro Terranova became the Artichoke King with a monopoly on small, “baby” artichokes, a Sicilian delicacy unheard of outside immigrant communities. Joe Profaci built his legitimate business empire on olive oil, beginning in 1920, around the same time my family was operating their own, far more modest import business out of their New York apartment. This niche product would go mainstream when Joe’s son, Joseph Profaci, Jr. and his Italian business partner, Enrico Colavita, founded an olive oil import business in 1978. American cuisine—and virgin olive oil—would never be the same.

Feature image credit: Herstellungsprozess von Olivenöl um 1600. After Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus (Netherlandish, Bruges 1523–1605 Florence),Jan Collaert I (Netherlandish, Antwerp ca. 1530–1581 Antwerp) – http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/427835

Very interesting. My Sicilian ancestors were all from Corleone. I’ve done some genealogy research but haven’t gotten a lot beyond names and dates. So far I haven’t found anything that would make me suspect a mafia connection. Is there some way to search your data by surnames?

LikeLike

Yes, I put my work on Wikitree. One place to start is on the category page for people from Corleone: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Category:Corleone%2C_Italia Feel free to contact me privately if I can be of any special help.

LikeLike

Justin I know there is a Cutrera olive oil company ,which part of Italy are they from thnxRudy Cutrera

LikeLike

The Cutrera family olive oil company out of Sicily is in Chiaramonte Gulfi. My family is from Corleone.

LikeLike