Was the Sylvan guard’s murder falsely attributed to the father of detective Flynn’s private stenographer? Correspondence sheds new light on the murder of Giovanni Vella.

In a letter dated 7 February 1911, James V. Ortelero asks for a favor from the superintendent of the federal prison in Atlanta, Georgia: obtain a murder confession from Giuseppe Morello.

According to his letter, Ortolero holds a confidential position in the office of the second deputy commissioner of police, William J. Flynn. But he’s not asking for his boss: the murder for which Ortolero hopes to obtain Morello’s confession is not under American jurisdiction. Neither can the crime be prosecuted by the Italian government, since it has passed the statute of limitations. Ortolero’s request is of a more personal nature, a matter of honor.

Ortolero and Morello are both from Corleone, where a Sylvan guard, Giovanni Vella, was killed in December 1889. If Morello confessed, it could do the imprisoned counterfeiter no harm, but it would be an honorable deed, clearing the name of an innocent man whom Ortolero says was framed for the murder, and is now on his deathbed in prison. The wrongly accused man is Ortolero’s father, Don Francesco Ortoleva.

According to Ortolero, his father was a highly respected man of means who was running for the position of chief of the Sylvan guard, in opposition to Vella. Ortolero describes Vella in the most positive terms, as a brave enemy of the Mafia in Sicily. Despite his excellent qualities, the two men disagreed politically, and argued publicly on a number of occasions. When a more highly placed figure in the Mafia ordered Vella’s murder, Morello and an accomplice carried out the assassination. Through a combination of public corruption and circumstantial evidence, Ortolero claims his father was found guilty and sentenced to prison for the crime. In one letter, Ortolero offers the warden a cash reward for the confession. Although it will not free his dying father from prison, it will clear his name.

James Ortolero was born Vincenzo Ortoleva on 3 November 1880 in Corleone, Sicily. The Americanization of his given name follows a familiar pattern for Sicilian immigrants: “Chenzo,” as he was probably called back home, sounds something like “James” to the English speaker. The modification of his surname is probably not significant. It may have been a deliberate move to obscure his identity from his countrymen, but this seems unlikely to have been effective. He was surely known to Morello and his associates, not only because they came from the same small town and lived in New York City at the same time, but because their families moved in the same circles in Corleone, and most of all, because of his father’s circumstances.

The Ortoleva family were landowners, descended from the Sicilian nobility through Don Francesco. One of his twice-great grandfathers had been a baron, and Francesco’s father was once mayor of Corleone. On his mother’s side, James was closely related to an aristocracy of Mafia families. One of his first cousins, once removed, is Paolino Streva, with whom Giuseppe Morello rustled cattle in the late 1880s. At the time of his death, Vella was investigating precisely this sort of activity.

The Sylvan guard, which Francesco Ortoleva and Giovanni Vella vied to run, were typically on friendly terms with local organized bands of thieves like Streva and Morello, with whom guards negotiated on behalf of the large landowners for whom they worked. Paolino Streva, Francesco Ortoleva, and Giovanni Vella were all from the landowning class.

According to Mike Dash’s account in his book, The First Family, Paolino Streva put Don Francesco Ortoleva up for election against Vella. Ortoleva was, in Streva’s view, a more pleasant and malleable chief than the honest and probing guard, and unseating Vella was preferable to killing him. Francesco was married to Paolino’s cousin, Laura Streva. Through intermediaries, Paolino had friends suggest to his cousin’s husband that he run. The day Ortoleva announced his candidacy, Vella got drunk and went to his apartment, and told his new opponent who was behind his run. The next day, Ortoleva withdrew from the election. That was when Streva told Morello to kill Vella.

James was just nine years old when his father’s political opponent was shot in the street on his way home from work. Morello fled the country three years later, in 1892, and moved to the American South with his family the following year. It’s not known when James Ortolero immigrated, or who may have joined him. James’ brother, Giuseppe, and sister, Emilia, both married in New York City, in 1903 and 1905, respectively. James married a woman from New Jersey, the former Eliza Mary Wright, in 1909.

In 1897, William J. Flynn, newly married, and until recently a plumber in Manhattan, embarked upon his government career. His first position was as an agent in the Secret Service. It was through the investigative work of Flynn and his operatives, working in collaboration with New York police detective Joe Petrosino, that Giuseppe Morello and his associates were charged with counterfeiting in New York in 1910. It is widely believed, and was the conviction of Flynn, that Morello was behind the assassination of Petrosino in Sicily in 1909.

Mike Dash’s account of James’ involvement in the United States begins in the summer of 1910, when he says that James went to New York with the hopes of convincing Flynn to help get his mother into the penitentiary in Atlanta, to visit Morello. Laura Streva hoped to extract Morello’s confession, herself, but Flynn suggested that he was not likely to confess to another crime while engaged in an appeal. According to Dash, Flynn liked the young man and offered him a job as his private secretary.

The warden in Atlanta, William H. Moyer, and James Ortolero exchanged several letters early in 1911. By degrees, the secret stenographer—his very position with Flynn was considered sensitive information—revealed his personal stake in Morello’s confession. In his letters, he never mentions any retaliatory murders of witnesses, following Vella’s shooting, though he claims that two women were “terrorized” into silence. Flynn, who would write about these events in his book, The Barrel Mystery, attributes as many as four more murder victims to Morello: Anna di Puma is named as a witness and subsequent victim in multiple accounts; Pietro Milone is identified by Mike Dash as another guard and “honest,” like Vella; and Michele Guarino Zangara is said to have been thrown from a bridge to his death after overhearing a conversation between Bernardo Terranova and his mother. No death records for any of these three, or for any other murders following Vella’s, appear in the Church records for Corleone, in the years between Vella’s murder and the debut of Flynn’s book in 1919.

Through the late winter and early spring of 1911, Ortolero followed up with the warden at intervals, eager for a report on Moyer’s efforts, but the warden’s replies amounted to excuses: in February there was no one he trusted to do the job, and then in March, he told Ortolero there was no qualified Italian interpreter available. In April, the stenographer wrote again to share what he had recently learned from a Secret Service agent (most likely Flynn): that Morello would confess as soon as he heard the result of his pending appeal. Their correspondence ends with a note from the warden’s secretary, acknowledging receipt of Ortolero’s last letter.

Dash tells us that Francesco Ortoleva, having served 21 years of a life sentence, was released from prison late in 1913, though it’s not clear how or why. Francesco appears in a ship manifest early in 1914, where it’s noted that he suffered from senility. He was 65. Don Francesco spent his remaining years in the United States with his family.

Morello’s appeal was denied. He remained in prison until 1920. Following his release, he spent some time in Italy to avoid a hit from a rival in New York. He returned to the city and enjoyed some prosperity during Prohibition, though he never rose to his former heights. He was killed in 1930. There is no evidence he ever confessed to Vella’s murder.

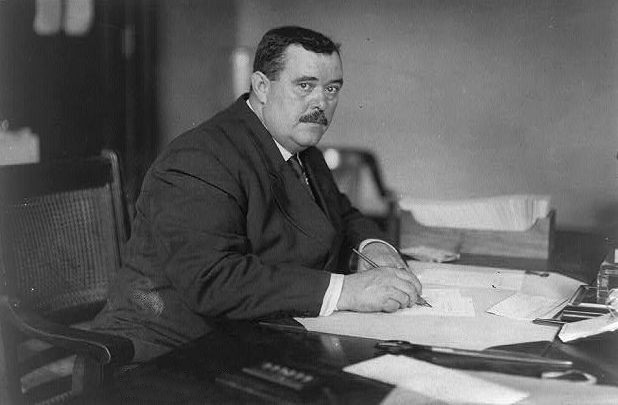

Feature image: William J. Flynn (1867 – 1928), the director of the Bureau of Investigation, by Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1909. Public Domain.

Sources:

Critchley, David. The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. 2008: Routledge.

Dash, Mike. The First Family: Terror, Extortion and the Birth of the American Mafia. 2011: Simon and Schuster.

Flynn, William James. The Barrel Mystery. 1919: James A. McCann Company.

Thomas Hunt has generously shared with me documents obtained from NARA including the following original correspondence between James V. Ortolero and William M. Moyer, the Warden of the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta, GA:

Ortolero, James V. Letter to Superintendent of the Federal Prison in Atlanta GA. 7 February 1911.

—–. Letter to William M. Moyer. “In re Guiseppe Morello, Register #2882.” 15 February 1911.

—–. Letter to William H. Moyer, Esq., Warden, United States Penitentiary, Atlanta, Ga. Dated 23 March 1911, stamped received 25 March 1911.

—–. Letter to William H. Moyer. 17 April 1911.

Warden, United States Penitentiary, Atlanta. Letter to James V. Ortelero. “In re Guiseppe Morello, Register #2882.” 9 February 1911.

—–. Letter to James V. Ortelero. “Desired confession of Guiseppe Morello, #2882.” 18 February 1911.

—–. Letter to James V. Ortelero. “Confession from Morello, register #2882.” 25 March 1911.

—–. Letter to James V. Ortelero. “In re Guiseppe Morello, register #2882.” 19 April 1911.

Leave a comment