When Mafia boss Joseph Colombo, Sr. became the leading voice in anti-Mafia propaganda, even “The Godfather” did what they were told. But his was not the first Mafia-backed Italian-American social justice organization in New York.

In 1970, Joseph Colombo, Sr., the boss of the New York City Mafia Family that bears his name, sponsored protests for months outside the FBI office that investigated his son, and told producers of “The Godfather” film not to use the words “Mafia” or “Cosa Nostra” in their scripts. His civic organization would become the loudest voice for Italian-American ethnic justice. But Joe Colombo’s League wasn’t the first civil rights organization with Mafia ties to emerge in New York City. Columbo’s political ambition grew out of disaffection with what is largely regarded as the League’s predecessor. In a bizarre twist, competition for the social justice spotlight was a part of Columbo’s downfall.

Beginning with the breakup of the 1957 Apalachin meeting in upstate New York, and continuing with US Senate hearings on organized crime, there was a resurgence of interest in the criminal organization.

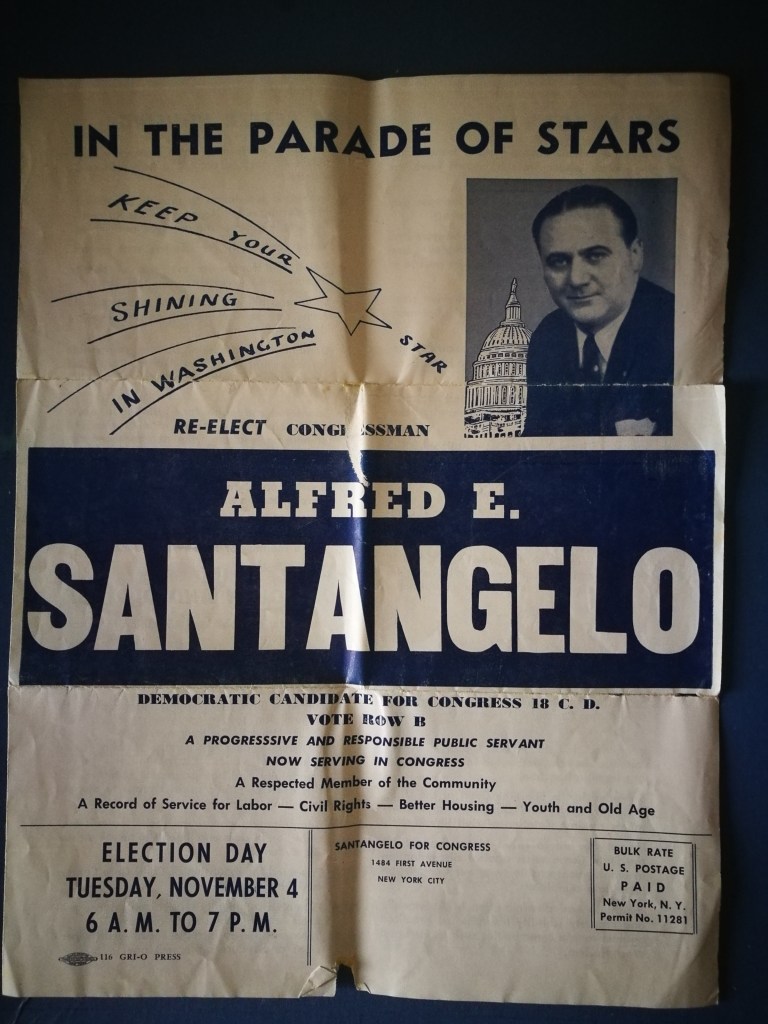

Alfred Santangelo’s American Italian Anti-Defamation League was founded in 1966 and quickly became the dominant political advocacy group in Washington for Italian Americans. While ostensibly they were formed to tackle defamation, their activities were primarily focused on shutting down reporting on the Mafia.

The majority of immigrants to the US from Italy arrived before 1924; in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, their grandchildren were moving into new suburbs, and leaving the old Italian neighborhoods in city centers behind. At the same time that Italian Americans were becoming increasingly integrated into mainstream white American society, the rising tide of reporting and sensational media about the Mafia represented the majority of what Americans knew about their Italian-American neighbors.

Organizations like the American Italian Anti-Defamation League sprang up in response, copying the language and methods of earlier, successful civil rights campaigns. The duplication was so faithful, in fact, that the AIADL was forced to change its name after a suit was brought by B’nai B’rith in New York State Supreme Court (Tomasson, 1967). The organization still exists as Americans of Italian Descent.

In its first year, the Anti-Defamation League succeeded in blocking publication of The Valachi Papers. Soon after, singer Frank Sinatra chaired a national fundraising event for the League in Madison Square Garden (Garden rally, 1967). The League’s success is likely attributable to its early president, Alfred Santangelo (1912-1978), a “rough and tumble” Democratic politician, and son-in-law of Lucchese Family gangster Calogero Rao (1889-1988).

Rao, a native of Corleone, Sicily, was an unindicted co-conspirator in Mafia boss Tommy Gagliano’s tax evasion trial in 1932, and a long-time business partner of Gagliano’s lieutenant and successor, Tommy Lucchese.Through his construction business he was also associated with one-time boss of bosses Giuseppe Morello. (Gagliano was an early Morello associate; both men were, like Rao, from Corleone.) In 1959, Rao took over a Lucchese Family lathing business. He married his first cousin, Maria Canzoneri, in 1912 in Manhattan, and they had three children. The middle child, Liboria, called Betty, married Alfred Santangelo around 1942.

Alfred Edward Santangelo was born on 4 June 1912 in New York City, the eighth of ten children. His father, Michele, was a carpenter from Potenza, Italy. He emigrated as a young man to New York City, where he naturalized and married Giuseppa Legiadro, Alfred’s mother (Marriage of Michele Santangelo and Giuseppa Legiadro, 1891; Michele Santangelo passport application, 1924). After their trip to Italy, Michele became a construction contractor. Most likely it was Michele Santangelo’s business relations that brought Alfred into contact with his future wife, since Rao and his brother, Vincent, made their fortunes as construction racketeers.

The Rao family spent the early 1920s in Corleone during the rise of fascism. A cousin of mine has related to me the gossip, passed down through her family, about Calogero Rao, who had left Italy as an impoverished farm laborer, returning from America as a wealthy, big shot mafioso. The Santangelo family visited their home town in Potenza in 1925. Calogero Rao and Michele Santangelo were both naturalized US citizens, so they were not subject to the restrictions on Italian nationals that came with new federal legislation in 1924: a product of America’s fascist surge.

The Santangelo family enjoyed an upper middle-class existence on Staten Island, sometimes with live-in servants, and all of the children received thorough educations. Alfred and an older brother, Robert, became lawyers; another brother, Paul, was a physician, and at least two of their sisters were school teachers. The youngest brother, George, a dentist, married Betty Rao’s younger sister, Rose, in 1943, creating a double-in-law relationship with Alfred and Betty.

From 1924-33, Robert Santangelo was a New York County Assistant District Attorney. Before the end of World War II, his younger brothers married into the Rao family. After the war, Alfred and Robert did criminal defense work. On his own, Robert defended Rao associate Joseph “Pip the Blind” Gagliano against narcotics trafficking charges. Robert Santangelo went on to have a long career as a judge.

Alfred went into politics, first winning office as a New York State senator, then as a US Congressman. He was a “go along to get along” guy in Congress, making useful friends in agricultural states who voted with him on issues of concern to Santangelo’s urban constituents (Oral histories and interviews, 1959). He continued to run a successful law practice and was already well-known for his defense of Italian American civil rights when, a few years after leaving office, he became the president of the new American Italian Anti-Defamation League (Gupte, 1978).

In the spring of 1970, residents of three East Side apartment buildings sued for relief from nightly picketing of the nearby FBI office, which Joseph Colombo Sr. targeted after his son, Joseph Jr., age 23, was arrested (McFadden, 1970). The FBI would not comment publicly on the newly formed Italian-American Civil Rights League (Colombo’s organization, not to be confused with the AIADL), but agents told a New York Times reporter that they believed the League was “a public relations front for organized crime” (Ferretti, 1971). Later that year, Joseph A. Colombo, Sr. was named Man of the Year for 1970 by The Tri-Boro Post, an unofficial organ of the IACRL (Grutzner, 1971). In reporting on the award, The New York Times described Colombo, Sr. as the reputed boss of the crime family formerly led by Joseph Profaci, free on bail after conviction for perjury.

While Santangelo’s organization had used his political ties to force the Mafia out of the media — he’d gone directly to President Johnson, who in turn directed his attorney general to stop publication of The Valachi Papers — Colombo’s used intimidation and violence. Attacks against The Staten Island Advance were linked to protests by the IACRL of publication of stories that used the words “Mafia” or “Cosa Nostra,” which its president claimed were inventions of the media, designed to smear Italian Americans as criminals.

The Italian Mafia historian Salvatore Lupo (2008/2015, pp. 161-165) has written that there are two strains of propaganda about the Mafia: that they are better than the rest of us, and that they don’t exist at all. They have the same goal, which is to deflect legitimate interest in Mafia crime.

In 1963, Joseph Colombo rose to leadership in his Mafia Family through the backing of Carlo Gambino, who Colombo protected from an assassination plotted by another Mafia boss, Joseph Bonanno. Bonanno wanted to take out not only Gambino but Lucchese and Stefano Magaddino, the Family boss in Buffalo. (A feud between the Bonanno and Magaddino families went back to their native Castellammare del Golfo, in Sicily.) The contracts for the murders came to Colombo, a new captain, from his boss Giuseppe Magliocco, whom the Commission — dominated by Gambino, Lucchese, and Magaddino — had not endorsed to succeed Profaci, the original boss, who died from cancer in 1962. When the murder plot was exposed, Magliocco was forced out and Colombo was given leadership of his Family, making him the youngest Mafia boss in the country.

Colombo was considered green for the position he held, and there was some question among his men whether he would defend any of them as ferociously as he had his son (Gage, 1971). A faction of his crime family led by Joe Gallo had been fomenting insurrection against Profaci and his loyalists since 1961. With the rise of the new boss’ Civil Rights League came a new target for Gallo.

“According to reports, when league members toured Italian neighborhoods in Brooklyn ordering merchants to shut down in honor of the league’s rally in Columbus Circle last June 28 (at which Colombo was shot), Gallo’s men followed close behind ordering the merchants to stay open” (Gallo this time, 1972).

Columbus Day festivities celebrating the Italian-American community are divisive precisely because of the values its proponents embrace. It could have been different. We Americans of Italian heritage could live as equals with our neighbors, just some of the many flavors in the melting pot, and take this day, as many of our neighbors do, to celebrate our people’s contributions: the real work done by countless Italians, from those who literally built the infrastructure of America, to Italian artisans who carve monuments to Columbus. Instead, the Columbus myth puts Italians first among European imperialists and colonizers. Denying our real Italian heritage of local feste devoted to patron saints, and the campanilismo that sustained our ancestors, a Genoese ship captain sailing under a Spanish flag was appointed by white, non-Italian Americans to represent us in all our diversity. I have a highly authentic gesture for Columbus’ supporters, taught to me by my grandmother, that I can show you.

It was just the right kind of celebration for a Mafia boss like Joseph Colombo. It was also his downfall. On 28 June 1971, Colombo was shot and paralyzed at the Columbus Day event he orchestrated. His shooter was immediately killed by Colombo’s bodyguards. He died seven years later from complications of his injuries.

It came out in the aftermath of the shooting that Joe Gallo had sought out Alfred Santangelo about ten days earlier and volunteered his own services and those of eight of his men to the Americans of Italian Descent. In 1972, the group was considered to be on its way out, overshadowed by Colombo’s League (Ferretti, 1972). Police intelligence suggested that Gallo’s intention was to create his own, competing organization similar to AID and the IACRL (Pace, 1972). Santangelo, at least, didn’t think that was the case. He was flattered by Gallo’s impression of him as a man of integrity, and thought Gallo uninterested in money, though he may have overlooked the ambitious gangster’s appraising eye. When Colombo first started his Civil Rights League, the Americans of Italian Descent cooperated with them, Santangelo told a reporter in an interview. However, he astutely saw Colombo’s group as agitators rather than peacemakers, and soon left the organization (Ferretti, 1972).

Police concluded that Jerome A. Johnson, who shot Colombo, acted alone. There were theories that Johnson was an agent of Carlo Gambino, and that Colombo had at some point offended Gambino when the older boss offered criticism of the League. However, many of Colombo’s supporters blamed Gallo. Gallo was killed a year later while celebrating his birthday at Umberto’s Clam House in New York’s Little Italy. The case was never solved.

Sources

Ferretti, F. (1971, April 4). Italian-American League’s power spreads. The New York Times. P. 64.

Ferretti, F. (1972, April 8). Italian group got Gallo aid for day. The New York Times. P. 34.

Gage, N. (1971, May 3). Colombo:the new look in the Mafia. The New York Times. P. 1.

Gallo: This time, the gang shot straight. (1972, April 9). The New York Times. Section E. Page 3.

Garden rally set by Italian League. (1967, August 30). The New York Times. P. 4.

Grutzner, C. (1971, January 22). Colombo named man of year by paper. The New York Times. P. 69.

Gupte, P. (1978, April 1). Alfred Santangelo, ex-legislator, dies. The New York Times.

Lupo, S. (2015). The two mafias: A transatlantic history 1888-2008. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. (Originally published as Quando la mafia trovò l’America in 2008)

Marriage of Michele Santangelo and Giuseppa Legiadro. (1891, November 12). Certificate no. 14752. Manhattan. DORIS. https://a860-historicalvitalrecords.nyc.gov/view/7974593

McFadden, R. D. (1970, June 6). Italian pickets at F.B.I. are sued. The New York Times. P. 19.

Michele Santangelo passport application. (1924, April 16). “United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99DQ-M76V-P?cc=2185145&wc=3XC5-7MK%3A1056306501%2C1056398701 : 22 December 2014), (M1490) Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925 > Roll 2479, 1924 Apr, certificate no 396850-397349 > image 507 of 707; citing NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.)

Oral histories and interviews: Fenno – Alfred E. Santangelo. (1959, June 11). The Center for Legislative Archives. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/legislative/research/special-collections/oral-history/fenno/santangelo.html Accessed 6 September 2018.

Pace, E. (1972, April 8). Joe Gallo is shot to death in Little Italy restaurant. The New York Times. P. 1.

Tomasson, R. E. (1967, October 6). B’nai B’rith unit wins injunction; American Italians can’t use ‘Anti-Defamation League.’ The New York Times. P. 36.