Every bad romance has at least two sides. The murder of Antonio Bonavita is no exception.

In Nicholas Anthony Parisi’s new book, Mafia Confession, we meet Eugenio Scibelli, who is the cellmate of the protagonist, Joseph Parisi. The great-uncle of the author, Parisi was in prison awaiting trial for the murder of Carlo Siniscalchi, a dangerous bootlegger whose territory was the South End of Springfield, Massachusetts. Scibelli was also wanted for killing a man, but his story was a very different one from Parisi’s, and I’d met Scibelli once before, in the pages of another family confessional.

I’ve had the good fortune to talk with the author and to preview Nick Parisi’s book. It was a narrative I knew well—from the perspective of the victim’s family. Pasqualina Albano, who is the “Bootleg Queen” I’ve written and talked about, inherited her position from her first husband, the slain “Bootleg King” of Water Street, Carlo Siniscalchi. Joseph Parisi, his rival, occupied a similar position among Calabrian immigrants in a neighborhood in West Springfield, just across the Connecticut River.

When Joseph Parisi was in jail in Springfield in the early months of 1923, he shared a cell with Eugenio Scibelli, recently captured in Jersey City, New Jersey, and wanted in the shooting death of Antonio Bonavita in Springfield on 4 December 1920. Bonavita was a shoemaker who did business on Water Street, the main thoroughfare of Springfield’s Little Italy. According to Bonavita’s granddaughter, who wrote about her family in 2017, the shoemaker was also a bootlegger and a rising star in the criminal firmament.

Parisi, the author, used his great-uncle’s diaries as source material, supplemented with local news coverage. Elaine Bonavita Jaquith grew up with her grandmother, who told her a version of events that she later published in The Mobologist’s Story. She writes that her grandfather was gunned down in a drive-by shooting, an event preceded by a home invasion that injured both of her grandparents. Nancy makes it clear the Mafia was trying to kill Antonio, if not why.

Not long after Tony Bonavita’s murder, his widow, Nancy, was able to afford both a large house and a small grocery store, a financial feat her granddaughter arches an eyebrow at.

The evidence is clear that her grandfather wasn’t killed in a drive-by, as Jaquith claims. There are other errors, both of fact (such as the birthplace of her grandparents) and the conclusions Jaquith draws from available evidence (for instance, that her grandfather controlled territory under the aegis of the Luciano crime family). The errors only grow larger, the closer she comes to her grandmother, both as source and as subject. It turns out there was a reason for that.

According to available sources, Nancy Bonavita was born Annunziata Maratea in 1902 in Monte Sant’Angelo, on the Adriatic coast, the daughter of a barber, Antonio Maratea, and his wife Giulia Grillo. They emigrated around 1916 and settled in Springfield, Massachusetts. Almost immediately upon their arrival, Nancy was subjected to advances by Antonio Bonavita, an immigrant from Fiorino, in the province of Avellino. Most of the Maratea family’s Italian neighbors in Springfield were from Naples, like Bonavita.

Jaquith writes that Bonavita was known to Nancy’s family as a criminal, causing them to reject him as a suitor, even after their sexual relationship became obvious. Antonio and Nancy’s first child was born prematurely and died in infancy in 1917, when Nancy was just fifteen years old. Only when Antonio threatened the Maratea family did they give consent for their daughter, still a minor, to marry him. By that time, Nancy was pregnant with their second child. Jaquith’s father, Pellegrino, called Peter, was born three months after his parents’ marriage in 1918. A third child, Frank, was born in January 1920.

The marriage was troubled, to say the least, and not only by the violence Antonio Bonavita invited into his life through his criminality. Nancy hated her husband and prayed for deliverance from her marriage. The couple lived at the January 1920 census on William Street, between the arteries of Main and Water streets in the South End. On the same block was Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, the spiritual center of the Italian neighborhood. Another neighbor on William Street was Eugenio Scibelli, with whom Nancy began a relationship that precipitated her husband’s terrible demise.

The assault on the Bonavita home that Jaquith writes about came before they moved in with Tony’s brother at 77 Wilcox. We don’t know when Nancy and Eugenio began their tryst, or when they left town together. Jaquith’s book does not mention any of this: not Scibelli or the affair, nor their connection to her grandfather’s death. The timeline of the most important events is not clear. Recalling that Nancy had a baby in January 1920, this all might have happened in a matter of weeks, or over the course of more than a year. There is no reporting I can find in Springfield newspapers of the armed invasion of the Bonavita home, only on what happened when they returned to the city.

Nancy and Eugenio, after some time away, returned to the South End. On the fourth of December 1920 Antonio ran into Eugenio, on foot near the corner of Main and William streets. Both men were armed and drew, but Antonio’s gun misfired, and Eugenio dealt the killing shot. According to his death certificate, Bonavita died nine days later from a pistol wound to the abdomen.

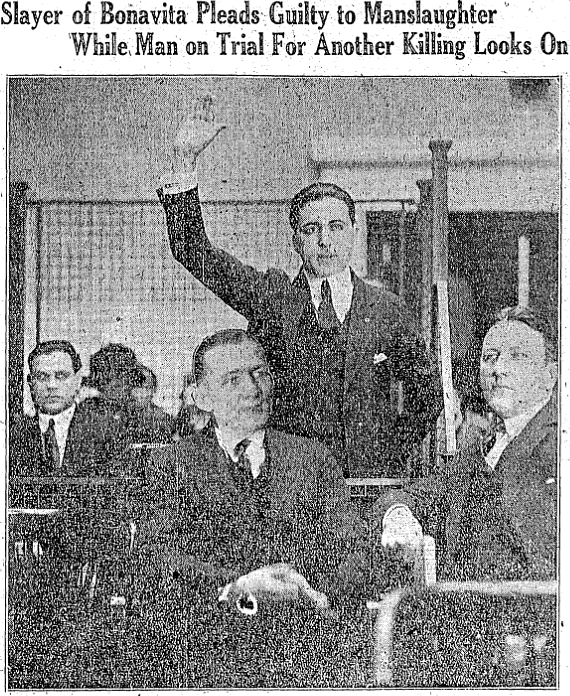

Eugenio Scibelli fled, but Nancy remained in Springfield. Two years later, Eugenio was arrested in New Jersey and returned to Massachusetts to face charges. It was reported that while on the run, Scibelli had taken up with a girl and was forced to marry her before his extradition. The judge at his trial determined that Scibelli had acted in self-defense in shooting Bonavita, but that he deserved some punishment for running off with his victim’s wife. He was sentenced to three to five years, and based on the birth dates of his children, was free in three.

Eugenio Scibelli was from Quindici, in Avellino. His bride in Jersey City was Adeline “Lena” Santaniello, a sixteen year old girl whose family was from the same comune. (Quindici is also the hometown of Pasqualina Albano.) They remained in the greater New York area and had three children. In a photo on her Find a Grave profile, Lena appears as a stout matron, smiling as she cuts meat at a small grocery counter. Both Scibelli and Santaniello are common surnames in Springfield, Massachusetts, but they are of no close relation to anyone I’ve run across in my research.

Nancy married again in 1922 to Joseph Vivenzio, another union that Jaquith never mentions. Around the time the widowed Nancy was supposed to be mysteriously flush with a new house and store, she and Joseph were listed as confectioners in the Springfield city directory. This occupation, utterly new to them both, was a common cover for bootlegging since on its face there is a legitimate need for sugar. During Prohibition (1920-1933) sugar was harder to purchase in commercial quantities because of the extremely high demand of the black market in alcohol production. Bakers and candy makers suddenly proliferated, not only because teetotalling Americans switched to sugar for the mood-enhancing effects, but as fronts to supply sugar to illegal distillery operations.

Another new, so-called confectioner of the time was Carlo Siniscalchi, Springfield’s “Bootleg King.” For reasons that no one has ever explained, Siniscalchi threatened and abused Joseph Parisi instead of selling him alcohol, leading Parisi to take his violent retribution. A year after Scibelli shot and killed Bonavita, Parisi shot Siniscalchi in his parked car on the same street, during the holiday shopping rush of Christmas 1921. (Jaquith mentions this shooting in her book, and remarks on its similarity to her grandfather’s murder.) Parisi was in jail for more than a year before being tried, leading to his overlapping stay, early in 1923, with the captured fugitive Scibelli.

By the time Eugenio Scibelli faced justice for killing Nancy’s first husband, she was remarried to Vivenzio. But her pattern of pursuing forbidden relationships with neighbors was about to recur. When she and Joseph Vivenzio applied for a marriage license, they already shared an address on Tyler Street, where their neighbor was her future husband, Timothy Driscoll. The Vivenzios moved away to Eastern Avenue, where they had their confectionery business, but the marriage was not a happy one. Joseph disappears from the local records. In 1928, Nancy and Timothy published their intention to marry.

Jaquith, the quixotic victim/protagonist of her own drama, describes a number of situations in which she is both naively innocent and at the same time, deeply enmeshed with more of the same kind of dangerous people as are in her family of origin. The principal example is of her son, the product of a relationship with a married former boxer she met while working with her cousin at Victor DeCaro’s cocktail lounge as a waitress. (DeCaro was the murdered son-in-law of Springfield boss Francesco Scibelli.) Elaine’s father used his insider position to pluck her from the jaws of the Mafia when she witnessed a crime at her workplace. In the chapters that follow, she ricochets blindly from terror to righteous fury.

Nick Parisi doesn’t reveal any insider knowledge of being a member of a Mafia family in his book, the way Jaquith does. The structure of Mafia Confession is solidly built around the murder of the bootleg king, with the author well outside the frame. Jaquith takes a risk in pointing the camera at herself, one that doesn’t pay off for her in the way she intended. The reader can see how she embraces the martyred position her Mafia family put her in, and turns her complicity into a virtue. As readers, we’re well aware of the distortions in Jaquith’s self-awareness, but it’s harder to intuit that her unreliability extends to what she has written about her family.

Family stories like those Parisi and Jaquith have used as their source material can be potent explanations of verified events, but they can also be misleading, when they’re the only evidence examined. It’s clear from the primary sources — including death records, censuses, and newspaper accounts — that the story Elaine Bonavita Jaquith heard from her grandmother was fabricated to conceal the active part she took in shaping her own life, and the consequences of her choices.

You can find both Jaquith and Parisi’s books on Amazon. For exclusive early access to the complete interview with author Nicholas Parisi, join Mafia Genealogy on Patreon.

Speaking of books, my first book on the Mafia has just been released. In Our Blood: The Mafia Families of Corleone, traces the origins of the Mafia and explains its organization and spread by following the mafiosi of Corleone, Sicily. Read more about my book here.

Sources

Allan J. Brookes [Obituary]. (2008, November 7). The Republican. P. B05.

Atto di matrimonio, Andrea Scibelli and Rosa Santaniello. (1875, July 17). Record no. 11. Archivio di Stato di Avellino > Stato civile italiano > Quindici > 1875 > Matrimoni

https://antenati.cultura.gov.it/ark:/12657/an_ua593626/5YerJ17 Img 8 of 23

Birth of Pellegrino Bonavita. (1918, July 9). “Massachusetts State Vital Records, 1841-1920”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QLKG-Z1BX : 7 September 2017).

Claffey, K. (1984, December 17). West side youth faces 7 charges. Springfield Daily News. P. 14.

Death of Antonio Bonavita. (1920, December 13). “Massachusetts State Vital Records, 1841-1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G1J9-VGP?cc=1928860&wc=M6S7-NP8%3A223963801%2C226041701 : 20 May 2014), Deaths > Deaths 1920 vol 98 Springfield-Stoneham > image 218 of 546; State Archives, Boston.

Draft registration, Eugenio Scibelli. (1918, June 5). “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9BRJ-LL4?cc=1968530&wc=9FHX-DP8%3A928311301%2C928697001 : 24 August 2019), Massachusetts > Ludlow City no 7; O-Z > image 1073 of 2459; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/171632958/eugene-scibelli: accessed 26 November 2023), memorial page for Eugene Scibelli (Mar 1897–6 Mar 1979), Find a Grave Memorial ID 171632958, citing Cemetery of the Holy Rood, Westbury, Nassau County, New York, USA; Maintained by BKGeni (contributor 46895980).

Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/171632962/adeline-scibelli: accessed 26 November 2023), memorial page for Adeline “Lena” Santaniello Scibelli (1 Apr 1906–16 Dec 1970), Find a Grave Memorial ID 171632962, citing Cemetery of the Holy Rood, Westbury, Nassau County, New York, USA; Maintained by BKGeni (contributor 46895980).

Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/206180117/severino-santaniello: accessed 26 November 2023), memorial page for Severino Santaniello (5 Aug 1866–Mar 1944), Find a Grave Memorial ID 206180117, citing Holy Name Cemetery and Mausoleum, Jersey City, Hudson County, New Jersey, USA; Maintained by Tami Glock (contributor 46872676).

Jaquith, E. B. (2017, May 20). The mobologist’s story: Wanted by the most powerful crime family, only her church family could save her now. Amazon.

Local news briefs. (1922, May 2). Springfield Daily News (Springfield, MA). P. 3.

Marriage intention. (1928, May 1). Springfield Republican.

Marriage of Joseph Vivenzio and Nunzia Maratea Bonavita. (1922). “Massachusetts State Vital Records, 1841-1925”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2ZM-5V61 : 24 November 2022).

Nancy Driscoll [Obituary]. (1991, February 20). Springfield Union-News.

1925 Springfield, West Springfield, Chicopee and Longmeadow, Massachusetts directory. Internet Archive.

Parisi, N. A. (2023). Mafia Confession: “King of Bootleggers” Murder. [Advance copy]

Parisi jury is still out. (1923, March 28). Springfield Republican. (Springfield, MA) P. 1+.

Santaniello household. (1920, January 9). “United States Census, 1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GR6G-DG6?cc=1488411&wc=QZJP-RNV%3A1036471401%2C1037732601%2C1037865601%2C1589332502 : 12 September 2019), New Jersey > Hudson > Jersey City Ward 6 > ED 155 > image 6 of 18; citing NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Scibelli gets light sentence. (1923, March 28). Springfield Republican. (Springfield, MA) P. 1.

Scibelli household. (1920, January 17). “United States Census, 1920,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRNN-69L?cc=1488411&wc=QZJY-QQN%3A1036470801%2C1037423801%2C1037582801%2C1589332873 : 11 September 2019), Massachusetts > Hampden > Springfield Ward 3 > ED 121 > image 37 of 48; citing NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Scibelli household. (1930, April 11). “United States Census, 1930,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RZ5-73B?cc=1810731&wc=QZFW-5C2%3A649437801%2C650319701%2C652305401%2C1589283975 : 8 December 2015), New York > Nassau > North Hempstead > ED 180 > image 29 of 38; citing NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002).

Although Eugenio Scibelli was a minor subject in my book, I learned a few new things about him. He did run off Bonavita’s wife, but I did not know he wasn’t the only one. Seems she got around with all her neighbors, four of whom you mention. If Scibelli didn’t shoot first, Bonavita may have killed half the neighborhood. Another good article as always! -Nick Parisi, Author of Mafia Confession.

LikeLike