In the days before “The Godfather” and “The Sopranos,” it was news accounts of crime that inspired the public imagination and created the image of the Black Hander.

Among non-historians, there is still a lot of confusion over what “Black Hand” means, and this is in large part due to an uncritical view of how the term was used when Black Hand crimes were at their height, from 1903-1920. Newspaper reporters, experts on Italian organized crime, and even the criminals themselves used terms including Camorra, Mafia, and Black Hand synonymously.

Mafia and Camorra are similar but distinct regional, ethnic gangs — small “m” mafias — that originated in Sicily and Naples, respectively. The Camorra is older than the Mafia and can be traced to the 18th Century, while the Mafia was most likely born in the early 19th C.

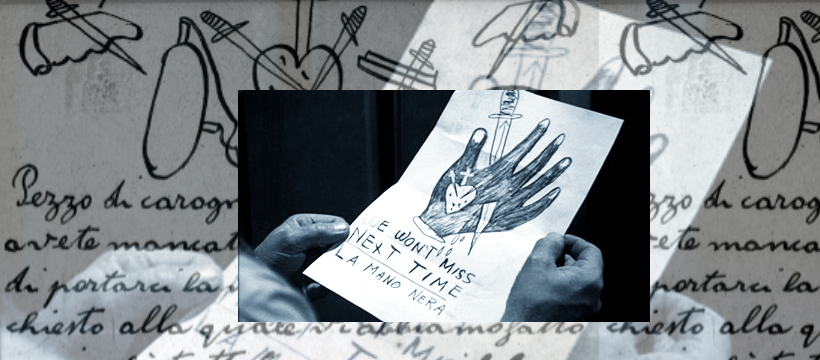

On the other hand, “Black Hand” is an extortion technique involving threatening letters and demands for money. A wide range of criminals and wannabes sent Black Hand letters, including some who were members or associates of the Mafia or Camorra.

In 1977, Thomas Monroe Pitkin and Francesco Cordasco published The Black Hand: A Chapter in Ethnic Crime which made the case that American newspaper journalists between 1903 and 1920 used the term “Black Hand” to describe any crime that struck the Italian community or was presumed to have been perpetrated by Italians, and sometimes more broadly to describe the Italian community as a whole.

“Black Hand” became the term of art for “Italian crime” in New York City newspapers after a 1903 Brooklyn case of extortion featured a letter signed “La Mano Nera.” (Humberto S. Nelli, writing a year earlier than Pitkin and Cordasco, attributes the origins of the term to the barrel murder committed the same year.) The sinister name was taken up by imitators of all descriptions. Novice and professional criminals, Italian and non-Italian, working alone and in groups of all sizes, sent Black Hand letters containing threats of kidnapping, murder, arson, and bombing, if a demanded payment was not promptly received.

Black Hand letters were soon being sent all over the United States, wherever there were Italians living. Newly arrived Italian immigrants in labor camps were particularly vulnerable and could be regularly squeezed for cash. The extortion cases most likely to be written about in the newspapers involved large demands from business owners in the Italian community. One Black Hand ring with an unusual recruitment method of inducting victims in good standing was based in Westchester County, NY, and went on trial in April 1903. Another group with the same membership policy was the Society of the Banana, based in Marion, OH, whose leaders were arrested in 1909. While this practice demands that victims learn the identity of their extorters, in the vast majority of Black Hand cases, the criminals remained anonymous.

In New York City early in the 20th Century, Italians found the same corruption and criminality they’d grown used to back home, only instead of the Mafia there was the Irish-dominated Tammany Hall and the vice districts they protected. Italians in Chicago found a similar situation prevailing. Everywhere in the United States, policing in Italian communities was ineffective, with language being just one barrier to justice.

The mainstream view of white Americans, who were having an isolationist era, was that new Italian immigrants were foreign and dangerous. Their xenophobic fears were played up in newspapers. Scientific thought leaders perpetuated the widely held eugenicist view that southern Italians were violent and criminal by nature. American patrolmen, for their part, held all the usual biases of their society, and in addition they were ill-trained for the job of protecting Italians from Italian crime. Italians believed that reporting crimes to the police only inflamed their extortionists’ ire. Their experience, both in Italy and America, taught the victims that criminals were more to be feared than the police.

The degree of overlap between Black Hand criminals and Mafia or Camorra associates is impossible to determine, since so few Black Hand crimes were successfully investigated, much less prosecuted. But the language that extortionists and those who wrote about them used was adopted for its visceral effects, not its accuracy in representing group affiliation or origin. In the case of the extortion of Dominico Lauricella in the ranch lands of Los Angeles County, California in 1915, mafiosi from Corleone, Sicily are described as both “Camorra” and “Black Hand” in a single article in the Los Angeles Herald. In one case cited by Pitkin and Cordasco, a Black Hand group called themselves “Carbonari,” after the early 19th Century Italian revolutionary movement.

Anton Blok, writing about the Mafia’s origins and defining attributes in 1974, claims that in 1900 Don Vito Cascio Ferro, the most powerful mafioso in Sicily, fled to New York City where he joined the Black Hand. Regardless, he was arrested for taking part in a counterfeiting operation—a traditional Mafia crime—in New Jersey in 1902. Cascio Ferro was sought again by police in connection with the barrel murder, an internal matter to Giuseppe Morello’s counterfeiting gang, which took place at Easter in 1903. Morello was the most powerful mafioso in the United States from 1900-1910.

Diego Gambetta, who applies economic theories to the Mafia, wrote in 1993 that the Mafia never took an interest in using the “trademark” of the Black Hand, including not just its name but methods and form. The Black Hand drew its name from the iconography of black hands, stilettos, skulls, dripping blood, and other gory and threatening illustrations that were often seen in extortion letters. According to Gambetta, the highly publicized “Black Hand” was too easily pirated and associated with petty crime to appeal to self-styled gentlemen like Morello and Cascio Ferro.

After all, it takes little effort to write an extortion letter, in contrast to carrying out the threats. Operators necessarily relied upon the fear the name and symbols engendered. For obvious reasons, extortionists did not sign their own names to their letters, so it was not their own reputations that made their victims pay, but that of the Black Hand.

Critchley believes Black Hand criminals and the Mafia were natural enemies. Salvatore Lupo, writing in 2008, acknowledges the evident hypocrisy in which “Men of Honor” found conflation with Black Handers offensive and the practice beneath them, but at the same time might participate in both kinds of rackets.

Further, mafiosi were not immune to predation by one another or other Black Hand criminals. In Chicago, Nelli wrote in 1976, Big Jim Colosimo was being extorted by Black Handers, prompting him to recruit his wife’s nephew, John Torrio, from New York, in a decision that he would live to regret.

Pitkin and Cordasco found a large overlap in membership between the Black Hand and the Mafia, but Critchley, writing in 2009 about the origins of the Mafia in New York City, concludes that the association between them was weak. In his view Giuseppe Morello was less involved in extortion than Flynn suggests. (Mike Dash, who wrote about the Morello-Terranova family in depth and is cited in the current version of the Black Hand entry on Wikipedia, gives little time to the topic of Black Hand in his 2009 book, The First Family, though when he does, he generally cites Flynn.)

Both the Mafia and the American society in which it thrives have changed a great deal during their years of coexistence. Early in the 20th C., the Mafia in Sicily and America was less centrally organized than it would become, but it still was identifiable as a type of organization with an origin, purpose, and rules. (To read more about the fundamental requirements of an organization, see How is the Mafia organized?) The Black Hand was not an organization. It was a criminal phenomenon of limited duration, a small set of threats that were sometimes carried out, and a media-created brand that instilled fear in its victims. This view is widely held by Mafia historians today.

Because Black Hand could be—and was—practiced by every ethnicity and in groups ranging from individuals to large, interstate bands, there is nothing that can be said about the organization of Black Hand gangs that is universally correct. Mafia and Camorra, on the other hand, can both be defined by their ethnic mandates for membership, hierarchical structures, and documented presence in Sicily and Naples, respectively, for generations. The Italian mafias are also distinctive for their broader range of methods, beyond those covered by the term “Black Hand.” In addition to kidnapping, extortion, bombings, arson, and murder, which were the traditional threats of the Black Hand, the Mafia and Camorra run protection rackets, lotteries, brothels, narcotics rings, and labor rackets, and commit other crimes of an organized nature which capitalize on the gangsters’ capacity for violence in underserved, often illegal markets within a defined territory.

Pitkin and Cordasco write that when Prohibition arrived, many of the same men who’d practiced Black Hand extortion moved on to the greener pastures of alcohol production and distribution. With so much money to be made in bootlegging, and the numbers of new immigrants dramatically decreased by war and quotas, actual Black Hand crime dropped off. As the dominant narrative about Italian crime shifted from extortion to alcohol, the language newspapers used to describe it changed, favoring words like “gangster” and “hoodlum.” Prohibition was unpopular, and the criminals of every ethnicity who grew rich serving alcohol to everyday Americans were admired as folk heroes who earned their success. The Mafia, with its purpose, numbers, and organization, excelled in the role.

Rackets diversified when Prohibition came to an end, and changed again when war brought domestic rationing of gasoline and foodstuffs. After World War II, the term “organized crime” came into fashion to describe the American Mafia. And in 1950, with the beginning of the Kefauver hearings, the word “Mafia” was revived in the press.

The Mafia had existed in the United States for more than 80 years, and been centrally organized for almost twenty. For most of its history, the Mafia was misunderstood with regard to its scope and organization. But Petrosino, or Flynn, or an American journalist calling the Mafia the “Black Hand” or vice versa does not mean that an objective difference cannot be observed between a method and an organization. The antipathy mainstream Americans had for the new wave of Italian immigrants — and the utility of fear in selling newspapers — better explain how Italian crime was portrayed in the press, and how it was perceived and described by experts.

Sources

Blok, A. (1974). The mafia of a Sicilian village, 1860-1960: a study of violent peasant entrepreneurs. Harper Torchbooks.

Critchley, D. (2009). The origin of organized crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931. Routledge.

Dash, M. (2009). The first family: Terror, extortion, revenge, murder, and the birth of the American Mafia. Random House.

Dickie, J. (2004). Cosa nostra: a history of the Sicilian mafia. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Gambetta, D. (1993). The Sicilian mafia: The business of private protection. Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

Lupo, S. (2015). The two mafias: A transatlantic history 1888-2008. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. (Originally published as Quando la mafia trovò l’America in 2008)

Makes fortress of home in fear of black hand death plot. (1915, November 23). Los Angeles Herald. P. 1.

May, S. (2017) Influenced transplantation: A study into emerging mafia groups in the United States pre-1920. (Unpublished PhD thesis, Coventry University). Retrieved 11 December 2019 from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8c83/47c18175b8dfd9c4a9c28b107273e466e897.pdf

Nelli, H. S. (1976). The business of crime: Italians and syndicate crime in the United States. The University of Chicago Press.

Obtain money by threats. (1903, April 6). The Buffalo Express (NY). P. 3. FultonHistory.com.

Pitkin, T. M. and Cordasco, F. (1977). The black hand: a chapter in ethnic crime. Littlefield Adams. Print.

I’m reading a book on the history of Naples. The author hypothesized thag Naples traditional Camorra clans got their start in the 1300s.

LikeLike

I’ve never heard a theory that made the Camorra that old! Who are you reading?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Naples 1343 by Amedeo Faniello

LikeLike

Fascinating. I’ll have to check this one out.

LikeLiked by 1 person